The perfumer who turns words into fragrances

In this third episode dedicated to perfume and literature, we meet Alexandra Carlin. The perfumer has forged a special relationship with words and smells, which she transcribes into magnificent fragrances. She believes that ‘perfumery has its own language’. Portrait: IFF. Visuals: Sébastien Plan – Abstraction Paris. Text: Valérie Donchez

Curious and sensitive, Alexandra Carlin is a perfumer who developed a special relationship with words and scents at a very young age. From literary studies to olfactory creations for some of the world’s greatest names, she has put her inspiration at the service of brands such as Bottega Veneta, Dolce & Gabbana, Karl Lagerfeld, Amouage and Diptyque.

For ALL-I-C, she talks about her relationship with words, her literary favourites and the creation of a pair of magnificent fragrances for Abstraction Paris: Our Own Backyard.

INTERVIEW

Has perfumery always been an obvious choice for you?

Alexandra Carlin: I started out studying literature with the idea of becoming a novelist. One day, during my Baccalauréat year, I turned on the radio and heard a perfumer talking about his craft. I didn’t know who he was, but his words resonated with me. It triggered a real calling. I knew straight away that I wanted to become a perfumer.

You were in the literary section. But to create perfumes, you have to take a scientific course. Was it easy to make the switch?

No, but I did it! After my A-levels, I went to an opendoor at the Institut Supérieur International du Parfum, de la Cosmetique et des Arômes Alimentaires (ISIPCA). Thanks to word of mouth, I heard about a scientific retraining course at Jussieu that enabled me to get the equivalent of the French baccalauréat S in scientific subjects. With this pass, I was able to enrol in a chemistry university, still with the aim of taking the ISIPCA competitive entrance exam. I passed on the very first attempt.

Where did you do your first perfume internship?

I did it at Dior, with the evaluators. At the end of my two-year trainee programme at ISIPCA, my tutor at the time allowed me to go to Robertet in Grasse for a three-month placement, which ended up lasting several years. I then met Maurice Roucel and he got me into Symrise.

Was your meeting with perfumer Maurice Roucel decisive in shaping your career?

More than you can imagine! At the time, he had signed L’instant by Guerlain and Kenzo Air. I also loved his Musc Ravageur by Frédéric Malle. So I called him up and said I was desperate to meet him. He started by giving me the cold shoulder. I told him I was a literary person, without knowing that he had a very scientific background, having come to perfumery through chemistry. He told me to come and see him. As we talked, the thing he noticed most about me was that I was a competitive track and field athlete. He himself was a competitive triathlete. That’s how he remembered me when he wanted to recruit a junior a few years later. Without knowing it, I was going to work with the perfumer who had inspired my vocation!

Was Maurice Roucel the mysterious perfumer you’d heard on the radio years before?

He was!

Don’t you have any regrets about moving away from writing for perfumery?

I don’t. When I think about a formula, I never have the anxiety of a blank page. The adrenalin kicks in when I get a project. I throw myself on a blank sheet of paper to write the first formulas. They’re like recipes with words, ingredients and quantities. For me, perfumery has its own language. I see materials as words. That’s how you memorise them in perfumery, literary or not. All the young people who learn perfumery memorise the fragrance notes with words and expressions. They learn to arrange them in alphabetical order. They start to smell them blind. You don’t know what you’re inhaling. You have five minutes to think. Everyone writes down what they feel. Then we share. These smells that we file away in our heads, we order them with words and adjectives. Words are always there. They are starting points for fragrances. An expression, a phrase will inspire me.

You’re starting a new adventure with IFF (International Flavors and Fragrances). Why did you make this choice?

I see it as discovering a new language with a new palette. It’s really exciting to explore new things, make them your own and integrate them into fragrances, into a story. I also like the positioning of IFF, a company that clearly describes perfumers as ‘perfume artists’. That’s how I see my job.

Would you say that you are a writer of scents?

Yes. I also see the perfumer as a director. To make a good perfume, you need a good story, it has to be readable. When the perfume designer Isabelle Doyen taught us at ISIPCA, she advised us to make a reverse dictionary. Under ‘bitterness’, we had to put all the materials that reminded us of bitterness or that could add bitterness to a perfume. I have the normal dictionary with the names of the materials and the reverse dictionary with the sensations, feelings, smells, colours, ‘green’, ‘pea’…

Do you write a lot?

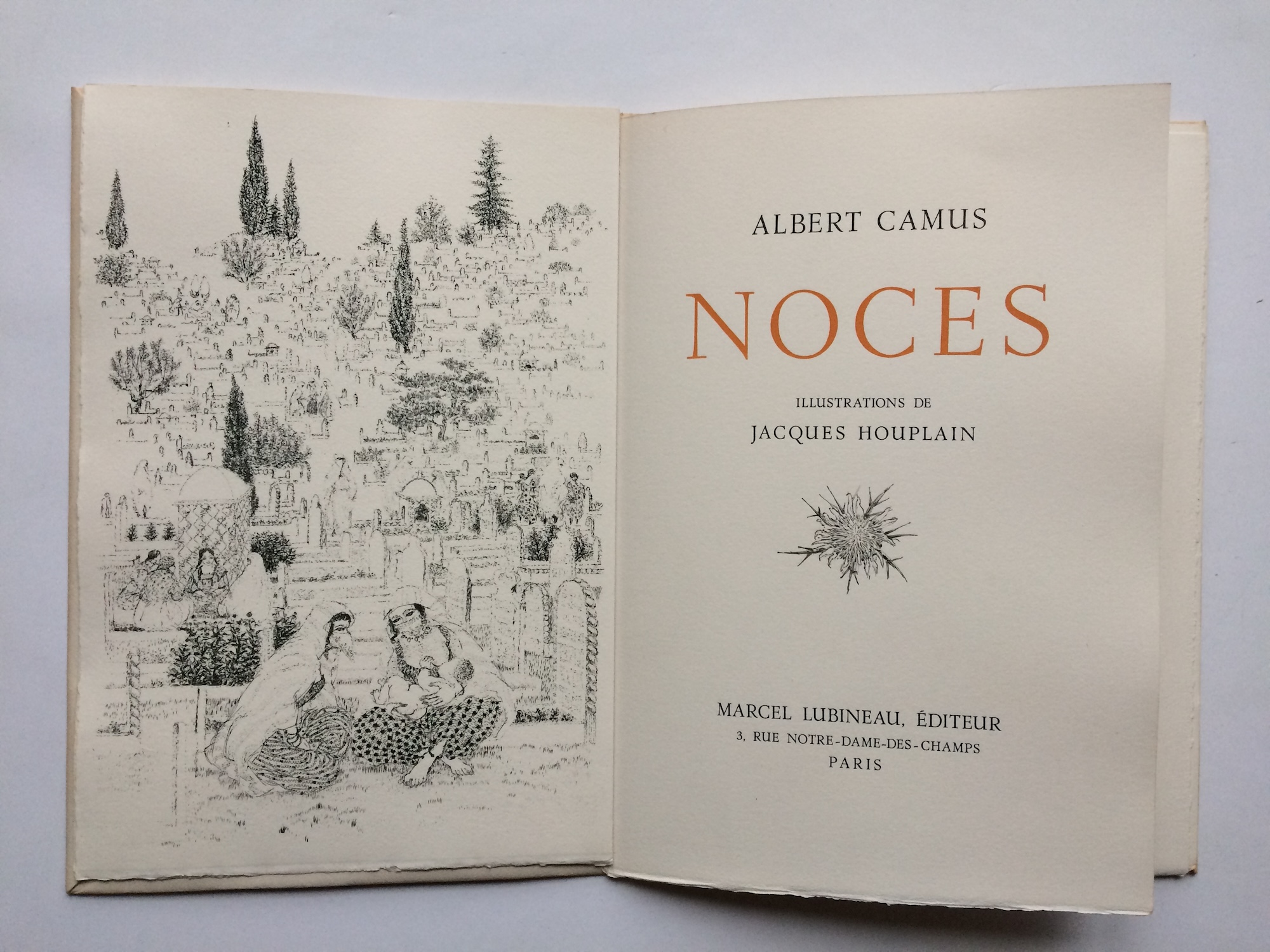

I love words. I put all my ideas into my phone. I’ve got lots of notebooks too. I write down agreements, things I want to work on because I watched a Top Chef programme or because a passage from a Camus novel inspired me.

When did literature first inspire you in perfumery?

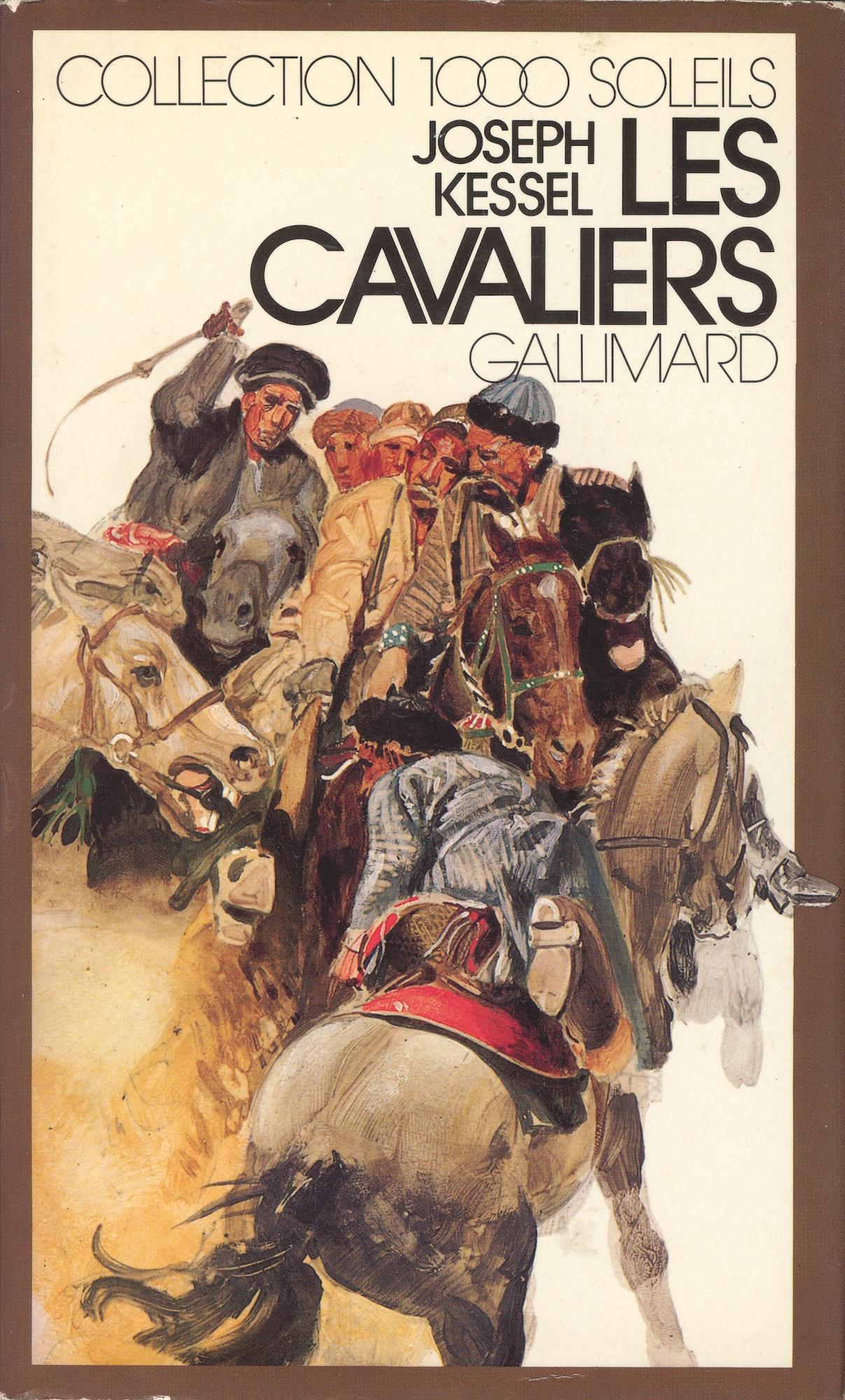

When I was doing an internship at Robertet. At the time, I wanted to translate Joseph Kessel’s ‘The Horsemen’ into a fragrance. In this book, as in many of Kessel’s works, there are a lot of scented passages. He describes the steppe with a smell of absinthe, caravanserais with tea, jam made with sheep fat, the smell of leather, the smell of blood, which also comes up a lot, and the smell of dust. It inspired me to create a perfume for the young perfumer’s competition. It was called ‘Sous la yourte’. I never sold it as such, but it’s got everything: steppe, animal notes, leather, dates… I also did Tipasa, inspired by Camus’ book Noces, a fragrance based on absinthe and immortelle. It describes the smell of Tipasa in Algeria. It was a stylistic exercise that I loved doing.

Tell us about Our Own Backyard, your two beautiful creations for Abstraction Paris…

I met Sébastien Plan, the creator of Abstraction Paris, in Grasse. He gave me carte blanche to imagine a pair of fragrances based on the idea of encounters and alchemy between people. I decided to create two fragrances with two of Kessel’s characters in mind, including a prostitute called Violette who appears in the novel Le coup de grâce. Then I thought of one of the main characters in Les Cavaliers, a rather boorish individual called Ouroz. I decided to create the two fragrances that make up Our Own Backyard with these two characters in mind.

Why Violette?

In Le coup de grâce, the character of Violette is the object of rivalry between the novel’s two heroes. One of them, Hippolyte, meets her and wants absolutely to possess her because she exudes something extremely animal and sensual. The story of her skin, of the sensuality of that skin, runs through the book. When Hippolyte realises that she is also the girlfriend of the great warlord he works for, a man everyone is looking for, he realises that he is in the thrall of this young prostitute who has no interest whatsoever in his boss. She’s only with him for the money. On the other hand, she is very much in love with Hippolyte, who is so disappointed that he takes his revenge on her.

Have you created your own story around Kessel’s characters?

In Our Own Backyard, I actually imagined a meeting between Violette and Ouroz, the character from Les Cavaliers, even though they never met in Kessel’s work. The two perfumes are very different. Violette’s is a musk that evokes her skin in the book, her complexion, her smell… Ouroz’s perfume is much more aromatic. I take up the idea of the steppe, absinthe and aromatics, and leather. The two fragrances have a common accord. It’s a universal skin accord that I worked on at Symrise, after doing a lot of research on skin odour to cover bad smells in particular. We had carried out studies on the smells of Caucasian, African and Eurasian skin. It was very interesting. I created a little accord that I put in both fragrances. That’s what links them.

If you could create a perfume inspired by literature, what would it be?

I love Nine faces of being, by Anita Nair. One day in my life, I’d like to make 9 perfumes inspired by this novel. It’s about a Kathakali dancer, a dance practised only by men in southern India, in Kerala. There are a lot of gestures and mudras. These gestures have meanings: they express emotions. The nine faces of being are nine emotions. I’d like to use olfaction to work on these nine emotions in the rhythm of the dance.