Nature is Claire Choisne’s muse and her battle

With her Carte Blanche collections, for which she has complete freedom to create whatever inspires her, Boucheron’s artistic director brings to life collections that push the boundaries of jewellery. New materials, new techniques, new ways of wearing jewellery – nothing can hold back her imagination. We met her in Paris during the presentation of the Impermanence collection, an ode to nature, its beauty, resilience and fragility. Isabelle Cerboneschi

Before entering the darkened room where the jewels were on display, the press was welcomed in silence by an antechamber decorated with a floral arrangement by ikebana master Atsunobu Katagiri. You had to get very close to discover that this gigantic bouquet, or rather a grove, did not date from that very morning but was slowly bowing out, some flowers bending under the weight of time, abandoning their petals, ready to fall apart and disappear after offering everything they had: their beauty.

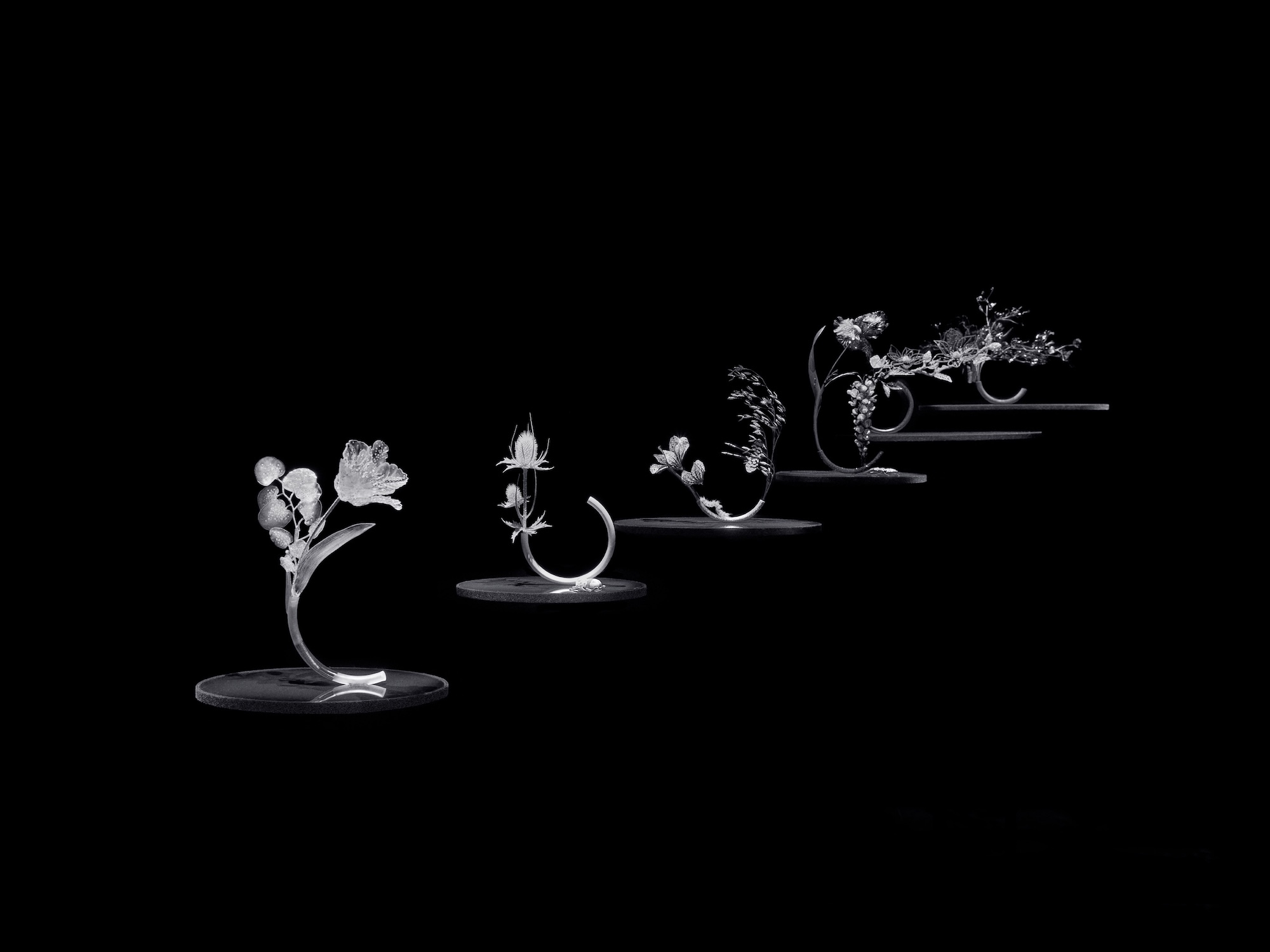

Impermanence. That is the name Claire Choisne gave to the latest fine jewellery collection she created for Boucheron, which was undoubtedly the most talked-about of the year. How can one remain unmoved by these six botanical compositions, like precious ikebana made from unlikely materials: borosilicate glass, nylon threads sewn with diamonds, Japanese brush hairs, white ceramic, black Corian, vegetable resin, black sand, Vantablack paint…

The word Compositions, representing each of the six sets, was deliberately chosen. Each piece is composed of several jewels – 28 for the entire collection – which form a bouquet in the spirit of Japanese ikebana. Composition No. 1, for example, is composed of a tulip, a branch of eucalyptus and a small dragonfly. “

The tulip can be worn as a brooch, as can the eucalyptus branch, and the dragonfly can be worn as an asymmetrical earring,‘ notes Claire Choisne. The translucent tulip appears to have been carved from rock crystal, but this is by no means the case. ‘We wanted to capture the extreme delicacy of the flower, and rock crystal did not allow us to do so.

So we made it out of borosilicate glass, which is stronger: it’s the glass used to make test tubes. It has been encrusted with diamonds,” explains Claire Choisne.

Composition No 1 ©Boucheron

The result calls for silence. How could it be otherwise? No words can describe what is happening here, as we are overwhelmed by this tsunami of beauty that illustrates the disappearance of nature.

The eyes move from one composition to another, but the brain cannot keep up: it does not understand what it is seeing. How was this thistle, which no one dares to touch, made? And this delicate little caterpillar? We asked Claire Choisne all these and more questions.

INTERVIEW

This collection is called Impermanence. What did you want to express through it?

Claire Choisne: It is a tribute to nature, which is disappearing before our very eyes. I chose to express this through six plant compositions inspired by Ikebana, and in order to make the notion of disappearance noticeable, I used a gradient of non-colours. The first composition is transparent, the second is white, and gradually black takes over until the last one, which is in Vantablack, and therefore completely black.

This isn’t the first time you’ve created a collection that sends a message in favour of nature conservation: you already did this with Or Bleu in July 2024.

Absolutely, it’s a bit of an obsession (laughs). As jewellers, our creations are made to last forever, and I wanted to freeze this impermanence forever. I like to work with the concept of time and capture ephemeral things that I find beautiful, in order to try to capture their beauty and stabilise it through jewellery. And that’s something we know how to do at Boucheron.

You worked with an Ikebana master to understand the secrets of this art. Did you choose the flowers that make up the collection?

Yes, as well as the compositions. It’s important to note that Frédéric Boucheron took nature as it was; he didn’t compose it to make his jewellery. So by choosing to create an entire collection like ikebana, which are very structured bouquets, I was initially off topic. But when I went to Japan to a school of ikebana that has been around for over 500 years to learn this art, I understood that Boucheron and the Japanese shared a common vision and a love of nature. Nature is not a means of creation: Ikebana means giving life to flowers once they have been cut. So it is not a story of still life that we have told with this collection, but of living nature. We have designed very light compositions with only two plants. We love nature, every plant, and we want to showcase them.

Isn’t it the body of the person wearing them that brings the jewellery to life?

For me, the jewellery is already alive, and when you see the magnolia necklace that seems to grow out of the shoulder, I think of life rather than a cut flower. The body is in the background: humans come after nature, which is the main subject of this collection. It’s a question of priority. Between nature and humans, I’ve made my choice (laughs).

Do you think customers will dare to wear these pieces?

I’m sad when jewellery is kept in a safe. So many hours are spent making it! Customers can, of course, leave the composition as it is at home and, if they feel like it, choose a day to take out the tulip and eucalyptus and wear them as brooches.

Can these six compositions be considered works of art?

Craftsmanship and art are often contrasted, but I love both and don’t want to choose between them. The notion of a work of art somewhat negates that of craftsmanship, but I am extremely proud of the craftsmanship that went into this collection. Let’s say it’s a hybrid, somewhere between the two.

Speaking of craftsmanship, all the jewellery is the result of extensive research. Was any piece particularly complex to create?

Perhaps the large thistle flower. It’s an extremely complex piece: we had to find the right person to make it, and there’s only one such person, who lives in the United States. This flower is a feat of engineering and a bridge between innovation and craftsmanship. What I asked the workshops to do was almost impossible: I had a thistle flower in my hand and I wanted them to reproduce it in a hyper-realistic way, with the same delicacy as the real thing, but without the prickles and set with diamonds. They managed to find a former MIT researcher, the only person in the world capable of 3D printing using bio-based plant resin. Each of the 600 diamonds set in the flower is held in a two-prong setting with a small ring at the end. Julie, one of the workshop’s gem setters, had the idea of sewing them with fishing line inside the spikes, one by one. The large thistle flower can be worn either as a brooch or as a crossbody necklace with a long cord. As for the small thistle flower, it can be detached and fitted onto a ring band.

Do you think you will use this technique in the future?

When working on the Carte Blanche collections, we learn new things and master new materials and techniques. Like a toolbox, this allows us to go further and avoid future constraints as much as possible, such as having to scale down a design. We will always find a metal, a material, a technique that will enable us to create the jewellery in the scale we have chosen.

What other unexpected materials were used for this collection?

To create the 600 or so hairs on the little caterpillar in Composition No. 3, my favourite, I asked for some Japanese brushes to be sent to me, which we cut and assembled. We also used borosilicate glass for the tulip in Composition No. 1. This is a very strong glass used for test tubes in physics and chemistry. I love rock crystal and whenever I can use it, I don’t hesitate to do so, but in the case of this collection, it would have given a thicker and therefore less realistic result. Borosilicate glass allows us to respect the actual volume of the setting. Before starting a collection, you have to take the time to understand what you’re looking for, and once you know, you have to give it your all to achieve that goal, allowing yourself to try new things or old techniques to get closer to your dream.

Speaking of dreams, Hélène Poulit-Duquesne, the CEO of Boucheron, gave you complete freedom to create the collections of fine jewellery presented in July, which are aptly named Carte Blanche. As Creative Director, how does it feel to be given permission to do whatever you want?

There are two sides to this licence. On the one hand, it’s the best gift I could have received. Without it, you can have great ideas, but they don’t go any further. On the other hand, when you have no framework and you start the creative process knowing that you can do anything, there’s a moment of vertigo. I know I can’t go wrong because this is fine jewellery, but I find myself wondering whether what I have in mind is a good idea or not. Anything is possible. Fortunately, the dizziness passes quickly and I can get down to business. It’s both brilliant and not easy.

You offer new shapes and ways of wearing jewellery. Is it important for you to reinvent the way jewellery is worn?

I don’t ask myself that question. I always start by thinking about what I want to do, the message I want to convey, and a collection is built from there. I wanted to pay tribute to nature, to show its impermanence, and I thought it would be interesting not to make jewellery straight away, but ikebanas, in shades of colour. Then we asked ourselves how they could be worn. Nature is not a tool: it is the end goal. Jewellery has adapted.

What new ways of wearing jewellery have emerged from the chosen shapes and symbolism?

The thistle, which is worn cross-body, is a new way of wearing jewellery. A cord is clipped onto the piece, and then the large branch and its flower are worn across the chest. There is also the magnolia branch necklace, which rests on the shoulder and extends outwards from the body. We would never naturally design a piece of jewellery like this, but as we were inspired by nature, its shape served as a starting point and a new way of wearing it emerged. As for the butterfly, which looks as if it has landed on a shoulder, it is held in place with a magnet that is slipped under the garment.

Is there a piece of jewellery that would be like a Holy Grail, a creation that is unattainable because of its theme, material or structure?

That’s what I strive for every time: a Holy Grail. Looking back at what I’ve done in the past at Boucheron, we see this same quest: how to question the precious. I’ve come up with several possible answers, and each time they resemble the Holy Grail: making flowers eternal, immortalising the beauty of water, warding off the impermanence of nature… I hope I never find the ultimate Holy Grail, so that I always have the desire to continue searching for it with the same motivation.

Is this concern with impermanence a philosophy of life?

When I talk about the collection, it’s part of an observation: nature is not respected for its true value. I see it disappearing and I want to encourage people to see its beauty, perhaps in the hope that they will then want to protect it. Then, in general, I find it difficult to come to terms with the notion of impermanence. It is something that can be frightening and at the same time it gives value to things. If we had the guarantee that everything would remain the same forever, nothing would have any value.

High jewellery is aimed at a very specific clientele, but because the collections are shared on social media, everyone has access to the images. Can and should this industry play a role in spreading the message about protecting nature?

This is my means of expression: I wanted to raise this issue through jewellery design, and that is what I want to convey with this collection. Jewellery is my means of communication. I don’t know if people expect this of me or not, but it doesn’t matter, I’m doing it anyway. I don’t know what kind of response this collection will get, but I feel it’s important to get this message across.

How do you feel when you look at the collection as a whole?

I worked on this collection for a long time and I know it by heart, yet I can’t get enough of looking at it. It’s addictive. It calms me. When I saw the pieces come out of the workshops for the first time, I felt a sense of relief. They existed: we had succeeded! And the fact that we had achieved this level of craftsmanship makes me proud. I was impressed by the jewellers. When I look at it, I get goosebumps every time. It touches something emotional. It’s like romantic poetry, in the true sense of the word: a beauty that is not sweet but dark.

Dark indeed: you can barely make out the last composition in this room plunged into darkness.

Because it is 100% black. It represents disappearance, the end of impermanence. It is composed of sweet peas, a poppy flower and a butterfly. The inside of the poppy flower has been lined with Vantablack, a material that absorbs 99.6% of light. Light is lost inside it and it is absolute black. The jewellers have crafted a magnificent poppy, which is entirely absorbed by the Vantablack, which seems to erase its volume. The tips of the flower’s pistils are set with micro-diamonds. They are like stars in front of a black hole before it disappears, before the end of the story.

For you, then, impermanence is not about fading away: it is disappearing?

It is more than that, it is an observation: we must take care of nature because it could disappear. But I see this as very positive because if it disappears, it will always reappear.

Do you see this collection as a message of hope?

Oui, pour moi, les étoiles, c’est le bonheur…