Sylvie Fleury, l’art du temps

The Geneva-based artist co-designed a regulator for the watch brand Louis Erard. The dial is inspired by the works she showed in Paris at the Palettes of Shadows exhibition in 2018, which featured paintings inspired by make-up palettes. During a long interview at her home, she agreed to look back on her career, her beginnings, her creative process and her unique perspective on things. Isabelle Cerboneschi

Two pink circles inside a black circle. This could be the description of a pop art work, except that this one is 39 mm in diameter and tells the time. It is the regulator that Louis Erard presented last January. This co-creation with Geneva-based artist Sylvie Fleury is a limited edition of 178 pieces.

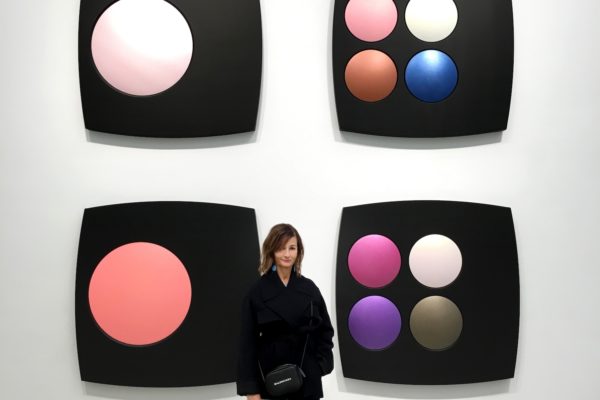

The regulator is a signature model of Louis Erard, and Manuel Emch, who took over the reins of the watch brand in 2018, regularly calls on artists or independent watchmakers to revisit it. But this model had something special about it. It made direct reference to Sylvie Fleury’s work and her exhibition Palettes of Shadows, presented at the Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in Paris in November 2018. The works were ‘shaped canvases’, created in the style of Frank Stella or Tom Wesselmann, inspired by make-up palettes but in XXL format.

Le Régulateur Louis Erard X Sylvie Fleury

These beauty accessories have always been part of Sylvie Fleury’s stylistic vocabulary, ever since her first exhibition at the Art et Public gallery in Geneva in 1993. She literally crushed them with her gold 1967 Buick Skylark, in a gesture that played on gender stereotypes. The ‘muscle car’, a symbol of masculine power, transformed by the artist into a glamorous accessory, reduced another accessory of femininity to dust.

With her works that subvert the codes of luxury, her Shopping Bags filled with real fashion accessories, casually placed in a corner, her golden supermarket trolley like a contemporary golden calf, her rocket – First Spaceship On Venus – in powder pink or covered in faux fur, Sylvie Fleury invites us with irreverence and a certain panache to question the excesses of consumerism. ‘Yes to all’, her illuminated sign shining on the roof of a building bordering the Plainpalais plain in Geneva, is a parody of an advertising slogan that sums up her message quite well.

Sylvie Fleury was unable to attend the presentation because she was busy hanging her works at the stand of the Zurich gallery Karma International at the Art Geneva fair. So we met over a cup of tea in the winter garden of her magical villa. It was an opportunity to talk about this watch, but not only that. During our conversation, Sylvie Fleury recounted her history with contemporary art, opening the door to the laboratory of ideas that is her mind. For her, art is a way of life.

INTERVIEW

When Manuel Emch, CEO of Louis Erard, asked you to co-create a watch, what was your reaction?

Sylvie Fleury I took this proposal as a little artistic challenge. Besides, I love objects and I enjoy designing them. I don’t want to become a designer, but I like the idea of having an extremely varied artistic practice. So it was easy for me to accept.

Did you immediately think of revisiting the idea developed in your exhibition ‘Palettes of Shadows’, which featured shaped canvases representing make-up palettes?

Manuel Emch and I had considered a bunch of ideas, but which ones? I don’t remember anymore. It’s been a while. When I get an offer like this, which is a bit offbeat and not directly related to my work, the idea often comes to me without me even thinking about it. And I might get inspired by the last thing I worked on.

The ‘Palettes of Shadows’ exhibition featured works in several shades: there was turquoise and midnight blue, white. Why did you choose pink, which evokes blush and adds a feminine touch to the model?

Quite a while ago, I bought a Rolex watch with a fuchsia dial. I loved that watch because the texture of the dial resembled lipstick. I probably mentioned this to Manuel Emch, and we got into a discussion about cosmetics. When you think of make-up palettes, the first ones that come to mind are black. But it’s true that black and pink are always a beautiful combination. I have often used pink to gender my work, but not in this case. I designed this watch with the idea that it would suit everyone. Some men might feel uncomfortable wearing a watch with pink on it, but hey, that’s just how it is…

Installation view, Sylvie Fleury – EYE SHADOWS, Salon 94, New York, 2017. Photo: Jeff Elstone. Courtesy: Salon 94 New York

Will there be a second edition in other colours, or is this a single release?

This model is a one-off, but I have another idea. It’s something I’d like to do. Maybe another time…

What was the biggest challenge, if there was one?

We didn’t encounter any difficulties. It came quite naturally and quite quickly, which for me is a sign that it was right. When you have an idea, you try to realise it and lots of technical or other problems arise, it’s an indication that maybe that’s not the right direction to go in. Or maybe it’s just laziness, a way of trying to avoid complications? Which, in the world of watchmaking, means something completely different (laughs).

This regulator can be seen as the ultimate reappropriation: it all started with make-up palettes, which inspired you to create shaped canvases, which in turn inspired this watch…

It’s funny because I’ve been using cosmetics palettes in my work for a long time, in other forms: I photograph them, I break them… I find these objects so beautiful! They look like little abstract paintings. I had been thinking for a long time that I should do something with these palettes, but just drawing or painting them wasn’t satisfying. Then one day I went to see a Tom Wesselmann exhibition in New York where there were lots of shaped canvases on display. And suddenly, these shaped canvases struck me as THE technique I needed to use. This happened about 20 years after I started using cosmetics in my work.

How did you achieve this result?

First, I had to transform and simplify the shapes of the palettes and then enlarge them. These are quite unusual works. In photographs, they are very graphic, but you can’t really appreciate their thickness or the work that went into them. You just see the shape and colour, but in reality, they are objects hung on the wall rather than simply paintings. It’s difficult to reproduce in a magazine because the artworks appear smaller and lose their appeal: I don’t like to imagine these pieces in reduced dimensions.

Yet that’s what you had to do to create the regulator.

With the watch, we had to reduce everything: the shapes are even smaller than the make-up palettes that inspired me. But it works well because it becomes something else.

Le Régulateur Louis Erard x Sylvie Fleury ©Louis Erard est une œuvre d’art que l’on porte au poignet. ©Louis Erard

Aesthetic diversion has always been part of your approach to art. Do you consider this dial to be an artistic act?

It’s difficult to ask me that question because, in my eyes, many more things than we think are artistic acts. First, we would have to define what an artistic act is… Perhaps it’s because I’m an artist that I say this, but I would answer yes: this dial is part of my palette. It’s a creation. This watch can be seen as a small abstract painting that you wear on your wrist, and at the same time you can read the time on it. But the fact that it’s a watch isn’t immediately obvious: the colour of the hands is the same as that of the dials.

In retrospect, when you look at the small coloured circles on a make-up palette, it seems obvious that they are shaped like dials. But no one had thought of that before.

I like that you say that because there’s something about minimalist art that I find fascinating: when you see a good piece of minimalist art, you think it doesn’t look very complicated, and at the same time, you don’t know how it got there.

I remember your first exhibition at the Galerie Art et Public in Geneva, where you presented broken make-up boxes on the floor.

I did worse than that! I brought my gold Buick and drove over it. That’s why my car was in the gallery. I brought it there just to do that. It was also a ready-made. I later presented it (in 2017, editor’s note) at Unlimited Art Basel, with make-up in front of the wheels.

Sylvie Fleury – Skylark (Buick Skylark 67) 1992. Buick Skylark 67, cassettes enregistrées, lunettes de soleil, foulard, porte-clés Chanel, magazines et rouges à lèvres. Vue de l’installation, Galerie Art & Public, Genève, 1992. Avec l’aimable autorisation de l’artiste.

Why did you decide to break this object in which we look at ourselves and with which we try to slightly alter reality?

I don’t think things are black or white. In my love for fashion, accessories and everything that makes up femininity, there are also contradictions. Sometimes you’re so happy to buy yourself a little cosmetic item, and sometimes you don’t want to fit into the mould. The funny thing is that after showing this piece, a magazine called Self Service hired me to be their beauty editor. They sent me cosmetics four times a year. I would receive a big box with all the new colours and it was fantastic! I would either break them or do other things with them. I really enjoyed it. When it came to choosing colours for my work, perhaps even before 1993, I always drew inspiration from cosmetic shades. There’s something absurd, when you think about it, in the fact that cosmetics companies conduct research to decide what will become the eye shadow, nail polish or lipstick of the season. Given that the perfume and make-up industry is one of the main driving forces behind consumerism, breaking a cosmetic product is a gesture that becomes political!

Sylvie Fleury – Skylark 1992. Vue de l’installation à Art Basel – Unlimited 2017. Photographe : Annik Wetter

You opted for shaped canvas, which is halfway between painter’s canvas and sculpture. You could have chosen to make it a sculpture. Why did you make this choice?

There is a very good reason why I didn’t choose to make it a sculpted object: the subtlety of the colours and shades of the make-up. I love choosing the colours we put in the Palettes of Shadows! They can be inspired by real make-up palettes that we rework. We can use pearlescent shades or matte colours, spray a little gold, silver or multicoloured glitter on top, I enjoy that. My gallery in New York didn’t want the title ‘Palette of Shadows’, but I liked it because the idea of the palette also refers to that of the painter.

These works are reminiscent of Renaissance trompe l’oeil, pop art, hyperrealism and Franck Stella’s shaped canvases. Do you see yourself in this lineage?

I have always claimed that my work is greatly inspired by art history, which is an inexhaustible source of resources for me. It’s important to look to the past in order to move forward into the future. I don’t deny that I was inspired by Mondrian, Yves Saint-Laurent, Marcel Duchamp and many others, and that I tried to recreate my own version of things that already existed, perhaps adding a little eye shadow (smiles).

Sylvie Fleury, Skylark 1992. Courtesy of the artist

Why were you attracted to ready-mades from the beginning?

To be completely honest, I didn’t go to art school and I didn’t know how to paint, draw or sculpt. But the first time I saw a ready-made, I thought to myself that I too could say things with objects without knowing how to paint or draw. I think that’s also why it became my language, in the same way that cosmetic colours became my palette. When I was with John (Armleder, who was her partner, ed.), who works a lot with chance and luck, he asked me what colour to choose for the monochrome he was going to place behind one of his Furniture Sculptures at the Rath Museum. It was a sofa with children’s clothes thrown on it. I told him to make it pink and red, because I was planning to wear my pink Valentino suit with my red shoes for the opening. And there you have it… The piece exists with a red monochrome. Another time, I advised him to use the colour of a Chanel nail polish called Vamp. Then one day he told me he was going to stop asking me to choose colours because I had developed a system that could no longer be considered random or a lucky guess. That made me think, and I realised that my colour palette was cosmetics.

Installation view, Sylvie Fleury, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg, 2005

Had you already started creating works at that time?

Not much. I had made my first Shopping Bags. But no doubt this interaction sparked something. Before that, I was doing photography, which is another way of saying things. I organised parties, I designed costumes, I always needed to create. From the age of 18 to 20, I spent two years living in New York. When I came back, my parents made me get a studio flat: they didn’t want me living with my boyfriend because it wasn’t proper. I chose a place in the Old Town and, as I didn’t have any money to furnish it, I went to the flea market. There was a whole series of slightly odd pieces of furniture that the seller was giving away: they were old items from a doctor’s office. So I turned my studio into a doctor’s office. And after that, I bought a small white station wagon. I put opaque stickers on the rear windows, little red crosses on the sides, and I always dressed in a doctor’s coat, white heels and fishnet stockings, sporting a punk hairstyle because it was the early 80s. I always felt the need to transform reality. I don’t know why, I can’t explain it, but it was something I enjoyed doing, something that made me feel good, and so it was just right!

Have you ever worked on the concept of parallel worlds?

Yes, when I did my retrospective at Mamco (‘Paillettes et Dépendances ou la fascination du néant’ [Sequins and Dependencies or the Fascination of Nothingness], in 2009, editor’s note). I placed clocks in all the stairwells, one above the other, with blue words that said ‘Revive’ and ‘Lighten’. I also had an idea that Christian Bernard (the first director of Mamco, editor’s note) couldn’t offer me for technical reasons: I wanted to open up part of the museum’s roof. He told me that he had to install air conditioning in the roof: why not take advantage of this to make an opening, like a small frame? I wanted to evoke the energy that came from the ground, rising up through the stairwell and then exploding into the air.

Sylvie Fleury, Installation view, Sylvie Fleury – First Spaceship on Venus, MAMCO – Geneva, 1996. Photo: I.M Kalkinnen. Courtesy: MAMCO Geneva – Private collection Sindelfingen

You mentioned that the idea of the watch face came to you ‘just like that’. How do ideas come to you? Is it something that just pops into your head, or is it more of a downward movement, an inspiration?

There was a rather magical period when I saw words that glowed: for example, I would see an advert and suddenly a word would stand out. I don’t know why. I asked myself a lot of questions to understand how and where ideas come from, and I don’t really have an answer, but I have tools that allow me to condition myself. For instance, I know that I need to be a little busy but not too busy, that it’s important to find the right balance between ‘doing a lot’ and ‘doing nothing’. And I need to stay very curious. Above all, I mustn’t shut myself away trying to find the solution at all costs because, in my case, that’s completely counterproductive. And then often, I have to forget… I have to forget that I’m looking for something. And that’s when it comes. It’s like those moments when you’re looking for a word or the name of an actor. You think and think. You can’t find it. So you give up, go for a walk, and suddenly your brain gives you the answer. It’s the same with ideas. A mixture of challenge and a kind of obviousness.

Le régulateur Louis Erard X Sylvie Fleury ©Louis Erard