Camellia in Chanel watches and jewellery

Gabrielle Chanel loved camellias so much that they became one of her emblems. The flower is found everywhere at Chanel: in fashion collections, accessories, beauty products, jewellery and watches. In this second episode dedicated to the camellia, we look at its place in watchmaking and jewellery. Model: Diane@elite. Make-up: Chanel. Photo shooting & Style: Buonomo & Cometti. Text: Isabelle Cerboneschi

How did the camellia come to Chanel? In the book Culture Chanel, we discover the first clue. ‘Gabrielle Chanel stole the camellia that Marcel Proust wore on the buttonhole of his jacket and hung it on the buttonhole of his jersey suits. She was moved to see Alexandre Dumas fils’s play, La Dame aux Camélias, performed by Sarah Bernhardt in 1913 at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Paris. The couturier, who was born on 19 August 1883, was 30 years old at the time.

That same year, 1913, she posed for a photo on the beach at Etretat. She had not yet cut her long hair and was wearing a jersey outfit of her own, consisting of a sailor suit and a long skirt. And what was hanging from her belt? A camellia. It was the first time we had seen the couturier wearing this flower, which would later become one of her emblems. For unknown reasons, the camellia moved from one theatre to another, from that of Alexandre Dumas to that of fashion.

With its minimal lines, voluptuous curves and regular arrangement of petals, this resilient flower of simple beauty was bound to seduce Mademoiselle and become an integral part of her own wardrobe and style. It wasn’t long before this symbolic flower was adorning clothes. The white camellia formed a magnificent contrast with the black of her dresses.

Gabrielle Chanel entre ses paravents de Coromandel en 1937. © Boris Lipnitzki/Roger-Viollet. © Archives privées/All rights reserved. Courtesy of Chanel

There are many camellias in Gabrielle Chanel’s successive houses: they can be found on candlesticks, in a rock crystal bouquet and scattered on the 17th and 18th century Coromandel screens that still adorn her apartment at 31 rue Cambon in Paris. She discovered these Chinese lacquer screens in 1910, when she was experiencing what was possibly her greatest love affair with Boy Capel. She continued to acquire some throughout her life, eventually owning more than thirty. ‘Lacquer is my element. It doesn’t jump out at you. I bought thirty-two folding lacquer screens, I gave a lot away, but I still have enough to wallpaper my house’, she said *.

The symbol of the camellia has outlived the couturier and can now be found in the formulations of Chanel cosmetics, and illustrated as a motif on make-up palettes. And when the House entered the world of jewellery and watchmaking, this symbolic flower became one of the major elements of the collections and also adorns the timepieces in a beautiful way.

Treasures of Camellias

This almost geometrically perfect flower, with its soft, regular contours, lends itself perfectly to being interpreted in jewellery. Thanks to the magic of the workshops, the camellia is transformed into precious brooches, pendants, necklaces and earrings. Camellia rings range from the simplest, such as the Bouton de Camélia, to the most sophisticated.

Camellia is present in many haute joaillerie collections, to varying degrees: in the 2018 Coromandel collection, inspired by Gabrielle Chanel’s precious screens; in Escale à Venise, which examined Chanel’s icons, the camellia in particular, through the prism of the Serenissima; and in Tweed de Chanel, which brought together in one collection one of the House’s favourite materials, tweed, around Chanel’s symbols, including the camellia.

But there was one collection in particular that paid tribute to this flower: the 1.5 1 Camélia 5 Allures collection, which was presented in 2019. This precious ode to Chanel’s emblematic flower was written in 50 Haute Joaillerie pieces, 23 of which were transformable, allowing for multiple wears that define an allure. Jewellery as Gabrielle Chanel conceived it when she created her first Bijoux de Diamants collection in 1932. ‘I want jewellery to be on a woman’s finger like a ribbon. My ribbons are flexible and can be taken apart. (…) My jewellery is never isolated from the idea of the woman and her dress. It’s because dresses change that my jewellery changes’, she said at the time**.

The Rouge Incandescent necklace, in white gold set with diamonds and a magnificent 7.61-carat cushion ruby, features a detachable camellia that can be worn as a brooch, as does the camellia adorning the Rose Poudré necklace, in pink gold and diamonds. In the same collection, a secret watch gave the camellia its most beautiful role: that of revealing the time on demand. And let’s talk about the time…

The camellia that tells the time

When Chanel entered the watchmaking business in 1987, the House decided to collaborate with G&F Châtelain, a manufacturer based in La Chaux-de-Fonds, before buying it out in 1993. Since then, Chanel has continued to strengthen its watchmaking division by calling on different professions. The first Chanel movements were created in 2005 in collaboration with masters, while the first in-house calibres were launched in 2016.

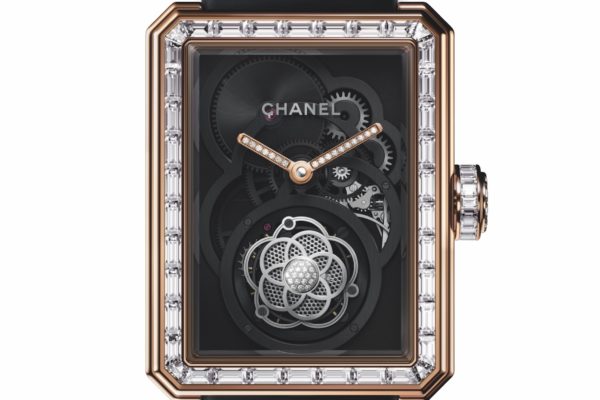

It was with a camellia that Chanel obtained its permanent admittance to the very closed world of grand complications: by presenting the Première Tourbillon Volant Camélia at Baselworld in 2012, created in collaboration with Renaud and Papi. This watch is driven by a flying tourbillon movement with a cage worked in the shape of a camellia, developed exclusively for Chanel by the Manufacture Renaud et Papi (APRP SA). The same year, this model won the prize for ladies’ watch at the Grand Prix de L’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG).

It was a camellia again, on the Mademoiselle Privé Camélia Brodé watch, that enabled Chanel to win a prize the following year at the 2013 GPHG, in the Métiers d’art category. This time, however, the emblematic flower was embroidered on the dial using a technique known as ‘needle painting’, with several different coloured threads worked in alignment to form a camellia in gradations of colour on a black fabric backing.

And it was again thanks to a camellia that during the 2017 edition of the GPHG, Chanel was rewarded for the Première Camélia Squelette watch in the ladies’ watch category. The movement of this timepiece, designed by the Studio de Création Horlogerie in Paris and then conceived, developed and assembled by the teams at the Manufacture Châtelain, illustrates a camellia. This second in-house calibre fully expresses Chanel’s vision of Haute Horlogerie. All the elements of the mechanism have been positioned in such a way as to blend into the background, leaving only the flower visible. A highly poetic watch that took 3 years to develop.

La montre Mademoiselle Privé Pique-Aiguille décor Dentelle s’inspire des outils des couturières. Avec son diamètre de 55mm de diamètre elle met en lumière les métiers d’art de Chanel ©Chanel Horlogerie

The camellia’s most recent appearance in Chanel watchmaking dates back to 2023. Arnaud Chastaingt, the Director of Chanel’s Watchmaking Creation Studio, was inspired by the seamstresses’ needle-pick to create the Mademoiselle Privé Pique-Aiguilles watch. This original 55 mm-diameter model showcased the House’s crafts, with five different themes. ‘Its oversized dial plays on excess and offers an incredible surface for expression. I dreamt of this creation as a blank canvas for the most audacious Métiers d’art’, explained Arnaud Chastaingt. One of the five models, the Mademoiselle Privé Pique-Aiguilles Décor Dentelle watch, was dedicated to the camellia. The camellia is a flower that can live for a thousand years. At Chanel, the camellia remains a beautiful symbol of the passing of time.

Source :

* Claude Delay, Chanel solitaire, 1983, Paris, Gallimard, chapitre X, p. 227

** Patrick Mauriès, Les Bijoux de Chanel, 1993, Londres, Thames & Hudson, pp. 23-24