Kari Voutilainen revives Zenith’s famous 135-O calibre

On June 2, Zenith launched ten chronometers powered by the famous calibre 135-O produced from 1949 to 1962, which was the most awarded movement in observatory chronometry competitions. The movement was restored and embellished by Kari Voutilainen and sold by Phillips in association with Bacs & Russo. A great adventure for watch lovers. Isabelle Cerboneschi

On 2 June this year, Zenith launched ten exceptional timepieces: ten chronometers powered by the famous calibre 135-O, produced from 1949 to 1962, which was the most awarded movement when observatory chronometry competitions still existed. These movements, which were in the vaults of the Zenith chronometry laboratory, belong to the history of the Manufacture, which has decided to continue their life by sharing them with some collectors. The case, the dial, and the restoration of the calibre and its decoration are all by the hand of master watchmaker Kari Voutilainen.

The idea was born in the minds of Aurel Bacs and Alexandre Ghotbi of Phillips in association with Bacs & Russo, who were responsible for selling the ten models. It took them a few minutes to do so. The price of these unique watches: CHF 132,900 – This wonderful adventure, which brought together three companies, lasted two years.

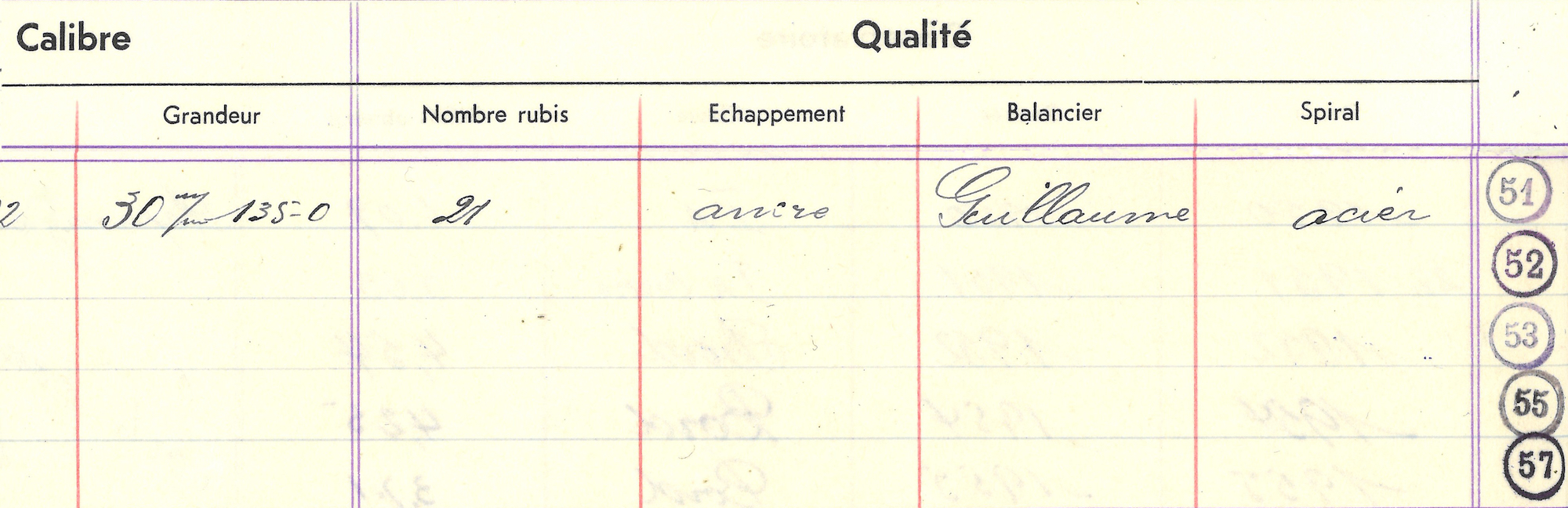

The 135-O calibre, which marked a milestone in the history of watchmaking, had been developed by Ephrem Jobin as early as 1945. Produced between 1949 and 1962, it existed in two versions: the calibre 135.O, intended to take part in the chronometry competitions of the Neuchâtel, Geneva, Kew Teddington and Besançon Observatories, and the calibre 135, its commercial version. With more than 230 chronometry awards, it holds the highest number of awards in the history of watchmaking.

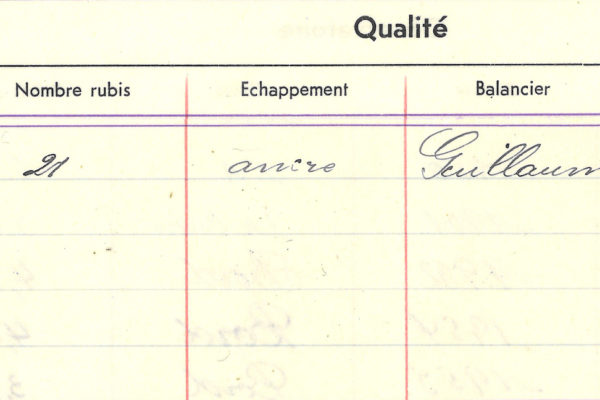

The 10 movements chosen belong to the years 1950-1954 and had been adjusted by Charles Fleck & René Gygax, two Zenith timekeepers with golden hands. As these calibres had never been commercialised, they lay untouched in their small protective wooden box in the Zenith archives. A master watchmaker was needed to restore them, embellish them and bring them back to life: Kari Voutilainen took up the challenge. Interview with Julien Tornare, CEO of Zenith, and Kari Voutilainen the day after the launch and sale.

INTERVIEW

This project represents two years of work and the watches were all sold in a few minutes. How do you feel about this moment?

Julien Tornare : We expected that, as soon as the announcement was made, the pieces would go very quickly because there were only ten of them. Last night, Kari Voutilainen, Aurel Bacs and I started receiving messages and we quickly saw that potential customers were going wild. When I went to bed, I felt a mixture of happiness, pride in what we had achieved together, but also a little nostalgia because it was over. Aurel and I thought that we should continue to see each other regularly and that maybe one day we could reunite the ten owners to keep the emotion alive…

Kari Voutilainen : When things happen like that, it’s proof that you’ve done a good job and that it’s right.

What kind of customer profile did you favour?

J.T. : The selection criteria are complicated, but the priority goes to people who will appreciate what Zenith has done by giving up pieces of history and heritage, as well as the exceptional work done by Kari on these watches. We also apply the principle of “first come, first served”. Aurel Bacs told us that they are not necessarily Zenith or Kari Voutilainen customers, although some of them are, but they are customers who appreciate this level of creativity.

K.V. : It is mainly people who are passionate about watchmaking who have bought them and not speculators.

How do you protect yourself from speculation?

J.T. :By knowing our customers. We know that they are lovers of this type of product and not people who need to resell their watch one or two years later to earn an extra 100,000 francs. I hope they will keep them for life. And that’s exactly the spirit of Kari’s customers. We didn’t do this project for financial reasons, otherwise we wouldn’t have done it, but for the love of fine watchmaking.

One has the impression that the manufacture is a huge Ali Baba’s cave, filled with treasures that you discover in a sometimes random way. This is the magic of Zenith?

J.T. : It’s true. After five years, I still discover things. It’s a brand with a lot of history. We knew that these movements were in the manufacture, we knew their history, because we work a lot with Laurence Bodenmann, our Heritage Manager, but there is a gap between knowing this and deciding to put these calibres at the centre of a new project. Zenith has lived a lot around the famous El Primero movement. When I arrived in the house, Jean-Claude Biver (who was the interim director of Zenith in 2017, editor’s note), asked me: “Is El Primero a good or a bad thing? I told him that it was an incredible asset but that we had to work on the weaker elements, and that’s what we did. We knew the legendary and unique aspect of the 135.O calibre, we knew that we could only do a project like this once. This calibre stands next to the El Primero and we can be proud of it.

Kari Voutilainen, were you already familiar with this calibre?

K.V. : Yes, in Finland there were three very popular brands in the 1950s until the quartz crisis: Eterna, Omega, and the most famous, Zenith. You can find a lot of Zenith pocket watches in Finland. I knew this calibre because I was in charge of the after-sales service for the commercial version of this calibre.

That’s the reason for this collaboration?

K.V. : Chronometry is one thing, but what is at the centre of the collaborations that I make is the human aspect. Alexandre Ghotbi (director of the watch department, continental Europe and Middle East at Phillips, editor’s note) is the key person in this project. We have known each other for a long time. I didn’t do this for the money and we have enough work as it is. I’m passionate about working with people I get on well with.

There are three companies involved in this adventure: a factory belonging to a large group, an independent master watchmaker and an auction house. How did you manage to harmonise this collaboration?

K.V. : It’s the human contact. And the LVMH group belongs to a family that respects its brands.

J.T. : I have worked for different groups and we are fortunate that Mr. Arnault, as a serial entrepreneur, gives us room to manoeuvre. This project, which would have required an infinite number of validations in another group, I decided on behalf of Zenith. That’s why we were able to have this spirit of collaboration. And then it’s mainly a question of people: we listen to each other, we respect each other. We debated, but there were no problems whatsoever. It was a Swiss compromise in the right spirit. I have only good memories.

These ten movements are historical pieces that were never intended to be commercialised. I imagine that there were internal discussions about letting go of heritage calibres?

J.T. : There were debates but quite quickly everyone realised that the best way to honour magnificent movements like these, made 70 years ago by exceptional people, was to give them a life. These calibres were made, prepared, trained for chronometry competitions. But the essence of a movement is to end up in a watch that will be worn. We have kept a few pieces that are part of the heritage and will never move. Only one more watch will see the light of day: a unique piece made of a material other than platinum with a different dial. After selling these 11 pieces, we will never market these movements again.

This work is similar to restoration. You had no right to make mistakes. What was the most difficult thing?

K.V. :We kept all the original elements without modifying them. We embellished the bridges and the plate. Decorating the wheels, cleaning the balance wheel, all this was risky. We had to think before we acted.

Is there anything about this movement that makes it impossible to invent it today?

K.V. : We could create this movement today but not the steel spiral balance which is the heart of it. Guillaume balance wheels are no longer manufactured, nor are steel balance wheels, but in terms of precision, it is the best.

Why was the Guillaume balance-wheel abandoned?

K.V. : Because the chronometry competitions were abandoned. During the quartz crisis, people thought that the mechanical watch was dead and the competitions stopped. The Guillaume balance is expensive to manufacture. It is a calibre that combines a steel balance spring and a bimetallic balance. But unlike traditional bimetallic balances, this one has a brass blade and a blade made of an alloy called Invar, a temperature-insensitive metal invented by Charles-Edouard Guillaume. This compensates for variations due to temperature changes.

There was no anti-shock system on these movements because they were not intended to be worn. Did you add one?

K.V. : No, and that was a choice. If we had added an anti-shock system, we would have had to modify the balance bridge and the adjustment system, but as we wanted to respect the original calibre, it was not possible. It is up to the customer to wear the watch with respect.

J.T. : We will explain this to all purchasers. They all have enough knowledge of watchmaking to avoid going to a squash game with their timepiece.

These movements had no face and you had to create it. In what spirit?

J.T. :There are certain similarities with the dials of the commercial calibre 135, but we wanted to give Kari as much freedom of interpretation as possible so that he could give it the most beautiful face.

K.V. : All the aesthetic choices are the result of discussions. It had to be a Zenith watch, a bit vintage but modern.

J.T. :… And we also wanted to find the spirit of Kari in this model. It was a quest for balance. Kari is one of the greatest master watchmakers but he is also a humble and modest person and his personality is reflected in the dial.

These movements are part of the history of watchmaking. How do you price such watches, knowing that the calibres that power them are limited, non-reproducible and reworked by a master watchmaker like Kari Voutilainen?

J.T. : It’s very complicated. We have taken into account several elements. The first is the fact that the movements we are selling are part of our heritage, and we cannot put a price on such pieces. Secondly, there is Kari’s exceptional work. Everyone knows the price of his watches and how well they do on the secondary market. We both know our clients very well, but the collaboration with Aurel Bacs and Alexandre was very interesting because they know the point of view of the collectors who buy pre-owned watches of different brands at auctions and the price they are willing to pay for them. In discussing this together, we all agreed on the price of 132,900 francs. This seemed to be the fairest price.

Can we expect more stories like this in the future?

J.T. : It will be complicated. I would like to have a 136, 137, 138 calibre in my drawers but that is not the case. It was an exceptional operation and it will remain so. This is also one of the reasons why Kari, despite her enormous workload, agreed to help us.

Kari, if you were offered a new exceptional project, would you go for it again?

K.V. : (laughs) We’ll have to see what it is… We have to concentrate on our business now, but if something that interesting came up, I wouldn’t say no.

Julien, do you plan to extend the collaborations?

J.T. : It’s like the limited edition phenomenon: you can’t do too much or you kill the magic. We receive proposals for collaborations every week. We don’t have a business model based on this kind of thing. It has to remain sharp, it has to make sense and it has to be done in small quantities to keep the mystery and the beauty.