Féminité du bois, thirty years on

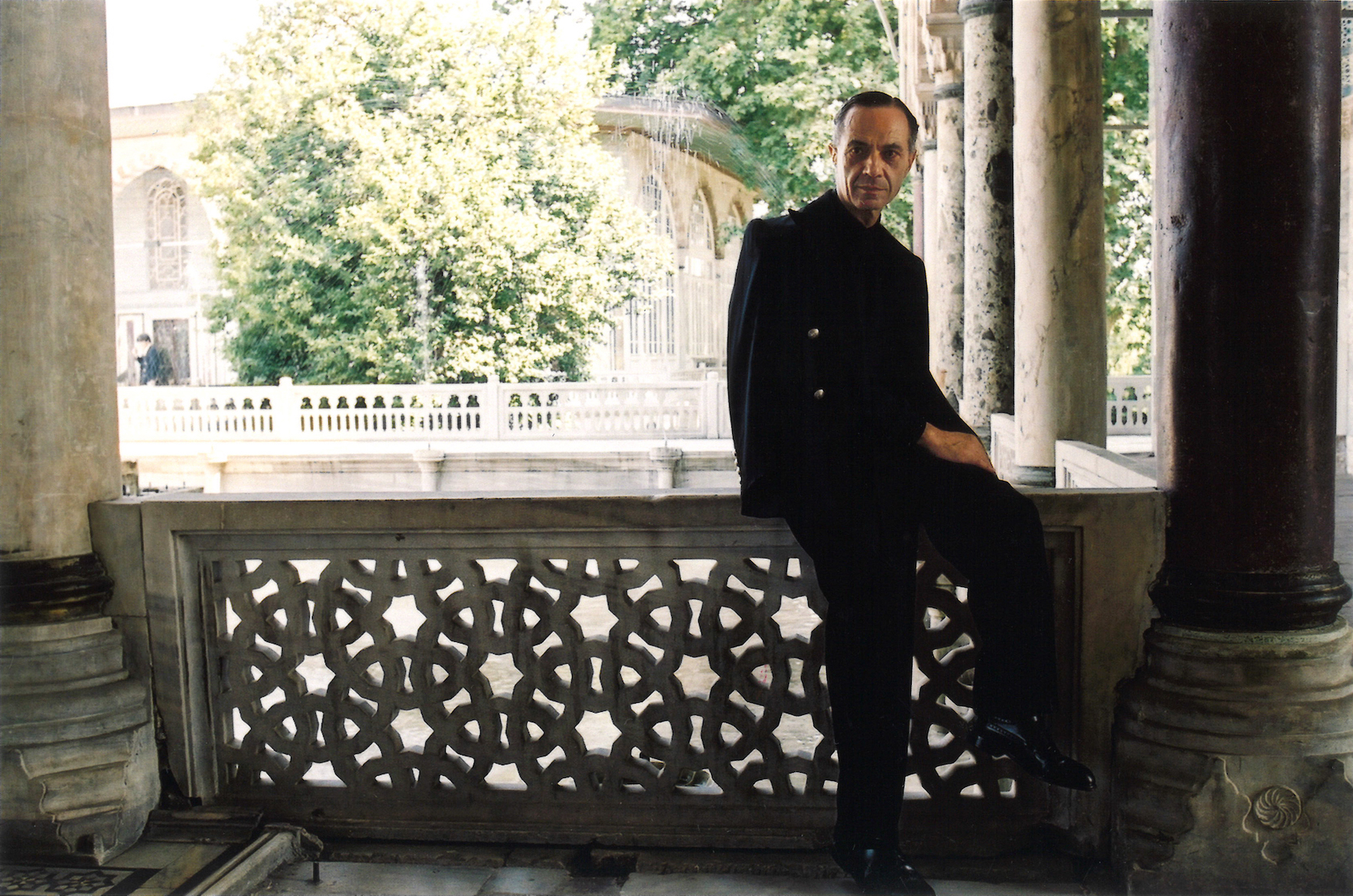

This fragrance created thirty years ago for Shiseido, shook up the codes of perfumery, with its soft, feminine woody notes, as reflected in its bottle. Serge Lutens tells us all about its origins. Isabelle Cerboneschi

I remember the thrill of discovering this fragrance as if it were yesterday. It wasn’t yesterday, but thirty years ago. First of all, it was the bottle that attracted me: lopsided with a hump and was an old rose colour. Serge Lutens, then artistic director of Shiseido, had long dreamed of creating a fragrance based on cedar. Under his aegis, two perfumers, Christopher Sheldrake and Pierre Bourdon, made his dream come true.

In Féminité du bois, there was nothing in line with what was being done at the time. Remember: 1992 was the year of the launch of Angel by Thierry Mugler, the first gourmand fragrance in history, and L’Eau d’Issey by Issey Miyake, which smelt of clean linen.

Féminité du bois, Serge Lutens’ dream fragrance, was the antithesis of the olfactory dessert of the former and the fresh water of the latter: it gave cedarwood the curves of a woman. Moroccan cedar accounted for 30% of the composition. Cinnamon, honey and rose softened its roughness, while vanilla, musk and benzoin gave it gravity and depth.

This revolutionary fragrance celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. Its new formula now includes 60% cedarwood, orange blossom and notes of plum. An opportunity to ask its creator about its origins.

INTERVIEW

You led the way in feminine woody fragrances with Féminité du Bois in 1992. How did this revolutionary fragrance come to you?

Serge Lutens : Wood was there long before I was. The cedar is said to be the only tree that God planted with his own hands. 1968 was the year of my first trip to Morocco, to Marrakech. My senses, all five of them, were, as one might say, in a state of sub-human fascination. It seems to me that at this point Morocco acted as a revealer. My sense of smell was dormant. However, it was all there; the nose was not blocked, but like the mind, too busy to be precise in one of the areas of sensuality. The more I wandered through the complex network of Marrakech’s alleyways, the more it seemed that the smell of cedar, at once animal, pastry-like, sweet and pervasive, was imposing itself on me. It was in a small metal box (previously containing throat candy) that a few shavings and a piece of this wood, before being transferred to another box, took their place in my mind and only grew there. The promise was in these words: “One day with you, I will make a perfume”. This promise was more akin to the wish of a child who would later aspire to fly an aeroplane, but who, in saying so, would only remember its speed, or of the same child who, in saying he wanted to drive a lorry, would only remember its power, or of yet another who wanted to drive a tramway, only to be put on the rails without asking himself where he was going.

It’s name brings to mind the sleeping Hermaphrodite, who lies facing a wall in the Louvre Museum, in Paris. Is this fragrance of that kind?

Whichever side it rests on, this sculpture or woman would be a nasty surprise for anyone hoping for precision. No, the wood is really feminine, or at least this one is, and no doubt even the rose belongs more to the boy than to the girl, who belongs to the sun and he to the moon.

What kind of femininity did you want to portray in Féminité du Bois?

I don’t really know. Perhaps the tree, the woman and myself are confused in this perfume.

In 1992, when it was launched, two other fragrances hit the headlines: L’Eau d’Issey, an ozonated and decorporated fragrance and Angel, which was the origin of gourmand fragrances. At the centre was Féminité du bois, just as revolutionary. You had to dare to launch a feminine woody fragrance, against all the codes of the time! What was your intention?

Daring is not a choice but a necessity, a way of surpassing oneself, of breaking out of the shackles, of letting out a cry that has remained in the back of the palate for too long.

Did you want to cross swords with a perfumery that was losing its soul to dilution?

I liked smells, but I didn’t like perfumes. Without really knowing how to put it, they bothered me, they were out of place. They were social products. However, perfumery as it was and as it is today doesn’t interest me any more. I think, dear Isabelle, that you and I talk about perfume to make it say something else. It has taken the place of someone or something in us, and perhaps to defend this unknown, we fight against the invisible; crossing swords in this case is crucial. We all take up our cross.

This fragrance is both mystical and sensual. Put like that, it sounds almost antinomic. Was this intentional?

Mystical and sensual are the right words. Antinomian, yes, because at the same time, these two entities combine and fight each other. Féminité du bois has a long history. Its development is tedious, but we’ll talk about it again, if you like.

In an interview, you said that you picked up a branch of cedar on the floor of a carpenter’s shop in a souk during your first trip to Morocco in 1968 and that you wanted to create a fragrance around cedar. Was it this first encounter that gave rise to Féminité du Bois?

I don’t think the origin of this fragrance is a wood, but a determination to use this material as a pretext. Getting away from ourselves, from what imprisons us, takes unexpected paths. Perfume is a bridge stretched between images and words. It’s scabrous because at the same time, I hope that in this hopeless advance, because we never reach it, we’ll arrive… but much more often we’ll fall.

You created this perfume for Shiseido at the time, but it has had many children: Bois de violette, Un bois vanille, Bois et musc, Bois et fruits, or Cèdre, its direct descendant. Is it fair to say that this fragrance is at the origin of auteur perfumery?

It was a personal and complex process, because I had to convince a group; opening a place in the least lively place in Paris was a real challenge! (The boutique Les Salons du Palais Royal, editor’s note). It was more the principle of getting out of this magma that was perfumery. But it was a lost cause, because the whole industry was quick to use marketing to get hold of an idea that up until then had only been personal, but that’s all in the past now.

Cedar wood is one of your favourite raw materials, found throughout your Riad in Marrakech. What does this wood evoke for you, to the point of including it in many of your opuses?

Does the image of a drill speak to you when it pierces a knot so tightly that to get through it, the tendril has to force it to such an extent that the pain smells so good it makes Freud look stupid!

Is this perfume a love story?

I can’t define the word ‘love’ enough. It’s an all-purpose word… Like “beauty”, for that matter. In both cases, these two feelings, if they live up to their promise, should surprise us, astonish us, overwhelm us. To define them or, through them, to define ourselves, would be to betray them.