Aure Atika, her name means “the light

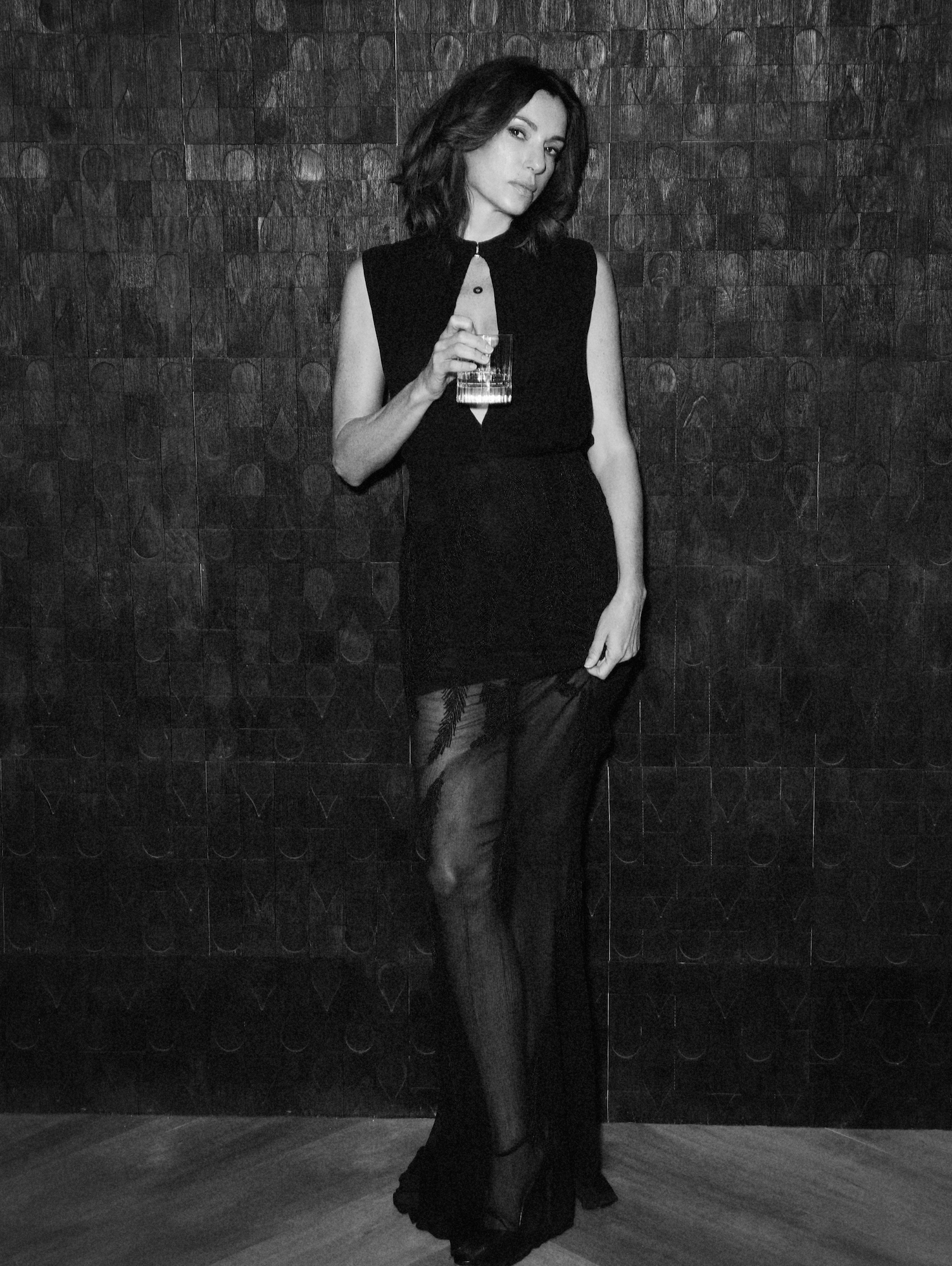

Since the beginning of the year, we’ve seen a lot the actress Aure Atika on the TV: she can be seen in the show Un homme d’honneur produced by TF1, broadcast on Disney+ since 23 April and in the film Voir le Jour on Canal+. In a long telephone interview, she talks about her job, which she loves, about the difficulties to work during a health crisis, her complicated childhood, and her way of getting through our complex times. Photographs: Michèle Bloch-Stuckens. Interview: Isabelle Cerboneschi

The French actress Aure Atika has a certain air of mystery. Her career spans the 360 degrees of a circle encompassing all genres. She has played in blockbuster comedies such as La Vérité Si je mens, OSS 117 Nid d’espion, in films by authors such as Abdellatif Kechiche’s La Faute à Voltaire, Jacques Audiard’s De Battre mon coeur s’est arrêté, in plays, in TV films such as the excellent Jonas, and in shows such as Un Homme d’Honneur, the French version of Your Honor, broadcast on Disney+ since April 23.

What is less known about her is that she writes beautifully: her first book Mon Ciel et Ma terre, published in 2017, won the Coupole prize. She recounts a dark childhood with her mother Odette, who was called Ode, a creative and unstable personality who was unable, in those very free spirited times, to resist the call of drugs. As for her father, he is the great absentee in her life: his identity is a mystery.

In her book, Aure, whose first name means light in Hebrew, has revealed her vulnerabilities, with modesty, but without cheating. Some scenes are unbearable and yet the actress embraces this difficult childhood that taught her freedom and independence.

The actress has built herself on her shortcomings and her strength, against all that her mother was, keeping from her only the taste for travel and freedom. She rejected addictions of all kinds, developing a rigour that could sometimes be seen as rigidity. It was not until she became the mother of her now 19-year-old daughter Angelica, and wrote this book, that she understood how abnormal her childhood was.

When she talks about the characters she plays, she often does so in the first person singular. As if they still inhabit her. Everything she is, her power and her flaws, she uses in her acting. She talks about this work she loves and about many other things in a long telephone interview.

INTERVIEW

In the mini-series Un Homme d’Honneur, you play Rebecca Riva, the wife of a mafia boss, Bruno Riva, played by Gérard Depardieu. How did you prepare for this role?

Aure Atika : You have to try not to fall into a kind of caricature. When I was told that my husband was Gérard Depardieu, I imagined that, being relatively younger than him, I had met him a long time ago, and that you don’t divorce a man like that. He’s an ogre! We had two children together, I’ve probably seen it all, but I did the best I could. I decided to play it softly at the beginning because I knew that the character would change and become very hard in the second part. I thought it was interesting to bring this contrast.

One would imagine that the wife of a mafia boss wears flashy and sexy dresses, but your character wears trousers all the time and is surprisingly sober. Was this intentional?

The look is the result of discussions with the costume designer. She made several suggestions and depending on what I wanted, we agreed on this look. In the flashback scenes, you notice that the younger character was wearing big earrings and dresses, but now she is 45, her son is in a coma: this is not a time when you want to do something crazy. I was very scrupulous about the choice of jewellery: she has several chains around her neck, several rings. I also wanted to have a hairstyle that reminded me of a Scorsese film in the Seventies’.

Women play a central role in the mafia. They are the ones who passe on to the children the idea that the organisation comes before anything else. Your character wants to save one of her sons so that he can escape this fate.

My character puts her child at the centre of her concerns. Simon, my son in the show, wants to become an architect and I want to save him from this line of mafia men: I’ll do anything to achieve this. This character may have unscrupulous methods, but she is above all a mother. Kad Merad, who plays the judge, and I face the same problem: “What are you prepared to do to save your children?”. This is the core of the show: the unconditional love that binds parent to child.

The series had a 19.4% market share. Did you expect it to be such a success?

It’s a great success. You never expect it, but we were hoping for it. It’s an adaptation of an Israeli series that did extremely well. The script is very well done and there is a good cast. We wished the audience to be there.

Did you have the opportunity to see Kvodo, the Israeli version?

In 2017, the Israeli version had been presented at the Series Mania festival, which is held in Lille and is dedicated to TV sshows from all around the world. That year, I was part of the jury and we gave the grand jury prize to Kvodo because this was so great, so smart! There was a political dimension that doesn’t exist in the French version. So when I was called last year to play the mafioso’s wife in the French adaptation, I immediately said yes!

You played in several TV shows and movies. How is it different to act for cinema and TV?

In a TV show, the characters are developed over time. You think he’s blue/pink and then you find out over time that he’s also a bit green/yellow. For an actor, it’s great because you can show several facets, you have more colours to express. Acting for TV is more intensive because you have to do more “useful minutes” per day. So you shoot much faster and you have to be more efficient. Sometimes we go too fast and this can be to the detriment of the direction. And when you go back to a film set, you find that everything goes too slowly (laughs). Cinema remains a space where creativity can flourish, where you have time to define the light, to direct the actors. You can afford to be more biased.

You are going to turn 51 this year. Is cinema harder for women of your age than for men?

I think that on the one hand there are more male roles than female ones in the cinema and on the other hand, for these roles, people want “fresh flesh”, so it is more complicated for an actress. A film made for television is more societal, the topics dealt with are closer to reality. That’s where you can find some beautiful roles for women.

Like in Marion Lain’s film Voir Le Jour, in which you play Sylvie and which can be seen on Canal+?

She only filmed women. It wasn’t out of militancy. She just wanted to make beautiful portraits of women in a neonatal unit.

This film was shot a year before the lockdown, but it highlights the dysfunctions of French hospitals, which have been exacerbated since the health crisis.

Caregivers have been complaining about their working conditions for several years. This was a reality long before the health crisis. For the purposes of the film, I spent two days in a neonatal unit, which was working quite well, but I was told how terrible it was in the other units.

During the lockdown you didn’t stop filming. How did this year go for you?

Two projects were postponed. The shooting of Un Homme d’Honneur finally took place at the end of June. It was like a silver lining! Then I played in the beautiful film of Aurélie Saada, the singer. Her first movie. My job is to act: I feel useless when I don’t work. Like other artists, I went through ups and downs, with days of sadness, asking myself: what kind of world are we living in and what are we offering our children? We live in difficult and challenging times and it’s harder for them…

Your daughter Angelica is 19 years old, how do you think you can help her?

She graduated from high school with distinction, she is now studying at the university. Her education was provided by her father and by me: once the parents have built up this solid foundation, the bulk has been done. All I can give her is love, material help and support in her choices. But I can’t tell her what to do. At 19, a child does not listen to advice. My uncle once told me: “Experience is a comb for bald people. “(laughs). I am happy because she is fantastic, very grounded, and I trust her. Whatever path she takes, I am proud of her.

Even if you started your career with author-driven films, Sam Suffit by Virginie Thévenet, Vive la République, by Éric Rochant, the one that many people remember is La Vérité si je mens where you played the voluptuous Karine Benchetrit. You have nevertheless managed to reconcile all genres, comedy, drama, series, TV films, personal films, theatre. How do you manage to do all that?

It’s a big gap that I claim. It was a struggle at the beginning. In 1996, I played in Eric Rochant’s Vive la République and Thomas Gilou’s La vérité si je mens at the same time. The two films were released a few months apart. The first didn’t work at all and the second, a comedy, was a blockbuster. I had to fight to prove that I wasn’t just a funny and sexy character. Even though I fully claim this role, because making people laugh is much more difficult than drama. In a comedy, you have to know how to keep a certain rhythm, whereas in a drama you have more time to express yourself. I think it’s great to play in mainstream films that make people laugh, even though my personal culture is more oriented towards author movies. I like to be at the service of a director who has a vision. Being at the service of an artist is something that thrills me.

In the film Rose, Aurélie Saada’s first film, you play with the legendary french actress Françoise Fabian. What can you say about it?

We don’t know when it will be released because we don’t know when the theatres will open, but it’s the very beautiful story of a woman played by Françoise Fabian. She is married and she has three children: I play her daughter, Grégory Montel and Damien Chapelle play her sons. Rose loses her husband and with the grief she will reinvent herself. How will this transformation affect her family relationships? This is a very universal theme. I loved making this film, even if the shooting conditions were difficult because we had to be Covid tested every 2 or 3 days to protect Françoise Fabian. Everyone wore a mask on the set, except the actors. It was the same for Un homme d’honneur. The problem is that you can’t see the humans anymore.

Do the sanitary masks worn by the people on the set change the way actors act?

No, but during the first few days of shooting on Un homme d’honneur, I felt less free in my body. On the other hand, it influences the human relationships: we talk to people we don’t see. It’s only when we all meet in the canteen that we recognise certain technicians by their tattoos or their clothes.

In 2017 you wrote Mon ciel et ma terre, which is about your childhood. Is it difficult to write about your own life, especially when the second main character, your mother, is no longer there?

The idea was to tell her story, to talk about that time, about our relationship… I chose to give voice to the child I was, who then became a teenager, then a young woman. I don’t find this difficult because the fact that my mother is no longer here has allowed me to say things. If she had been alive, I would never have written a book about her, I would have found that indecent. One day a shrink said to me: “But why are you so protective of your mother?” I think that what I transcribe in this book is the love I had and have for her, even if I tell the hard, abnormal things, you can feel my love. I didn’t want to be too critical. I don’t know if it’s a self-imposed censorship.

When you were a child, you were already protecting her, reversing the roles, as if you were the mother. In retrospect, when you became a mother, did the anomaly of certain situations become apparent to you?

Absolutely! I think of the day when she came back from India and said to me: “come, I’ll show you something”. She broke the wooden shelf she had brought back and there was a kilo of opium inside. For me, as a child, it was a nice story, but as I was writing it, I thought it was crazy! How reckless! If she had been caught at the border, she would have spent 20 years in prison in India, while she had a child in France! I realised all this while writing it. Putting words on all that made me feel better, even though that wasn’t the point at the beginning. It was no longer my little secret burden. I could move on. I didn’t judge her, but I realized how unresponsive the decisions she had made were. If she had acted differently, my life would have been different.

We build ourselves as a mirror of our childhood or in reaction to it. What gift did your childhood give you?

I don’t think there is much in life that shocks or impresses me. Because I’ve been through some very complex things, I have a certain taste for adventure, whatever it may be. I didn’t have a boring childhood, it was colourful. I was given so many gifts in fact! My independence, my ability to say no, my taste for travel, for beauty and aesthetics, my mother gave them to me. My taste for work, for things well done and my sometimes rather severe rigour, I built them in opposition. I refuse addictions of any kind because I saw the effects of drugs on her. If I have one regret, it’s the fact that she didn’t support me to do long studies. A more stable framework would have made me feel more secure and I would have been less fragile. But children and parents do what they can. She always trusted me and gave me a lot of freedom.

You have made short films. Did you feel like making one with this story of yours?

A producer would tell me that he wants to adapt and produce it, I would give this story to a scriptwriter, but I don’t have the energy on my own. I don’t want to limit myself to this story.

Did this first book make you want to write a second book? Perhaps about the father figure, who is the great absentee in your life?

Thank you for suggesting it. I don’t know… I’m currently experiencing a writers block, I can’t write, but if I get the taste for it again, there are other themes that I would like to explore. I’m a bit fed up with these family stories.

Living in 2021 is difficult for everyone. What are your secrets for getting through this time?

Like a lot of people, I’ve been through “ups and downs”. What saved me were the moments when I worked, saw friends, the love of loved ones, the little joys. In January, I couldn’t take it anymore. Paris, without the cinemas and theatres, is like living in Limoges, but without the advantages, nor the nature next door. There’s no point. I went to Polynesia almost on a whim. I had acquaintances and family there and it did me a world of good. I stayed there for a month, travelled around the islands, read a lot, met some fabulous people. Over there, the pandemic is not experienced in the same way: there is sunshine, space, they have very few cases. Since then, I feel much more solid and confident. Having faith in the future has become very difficult. So like many people, I’m living in and appreciating the moment.

Make-up + hair: Delphine Goichon