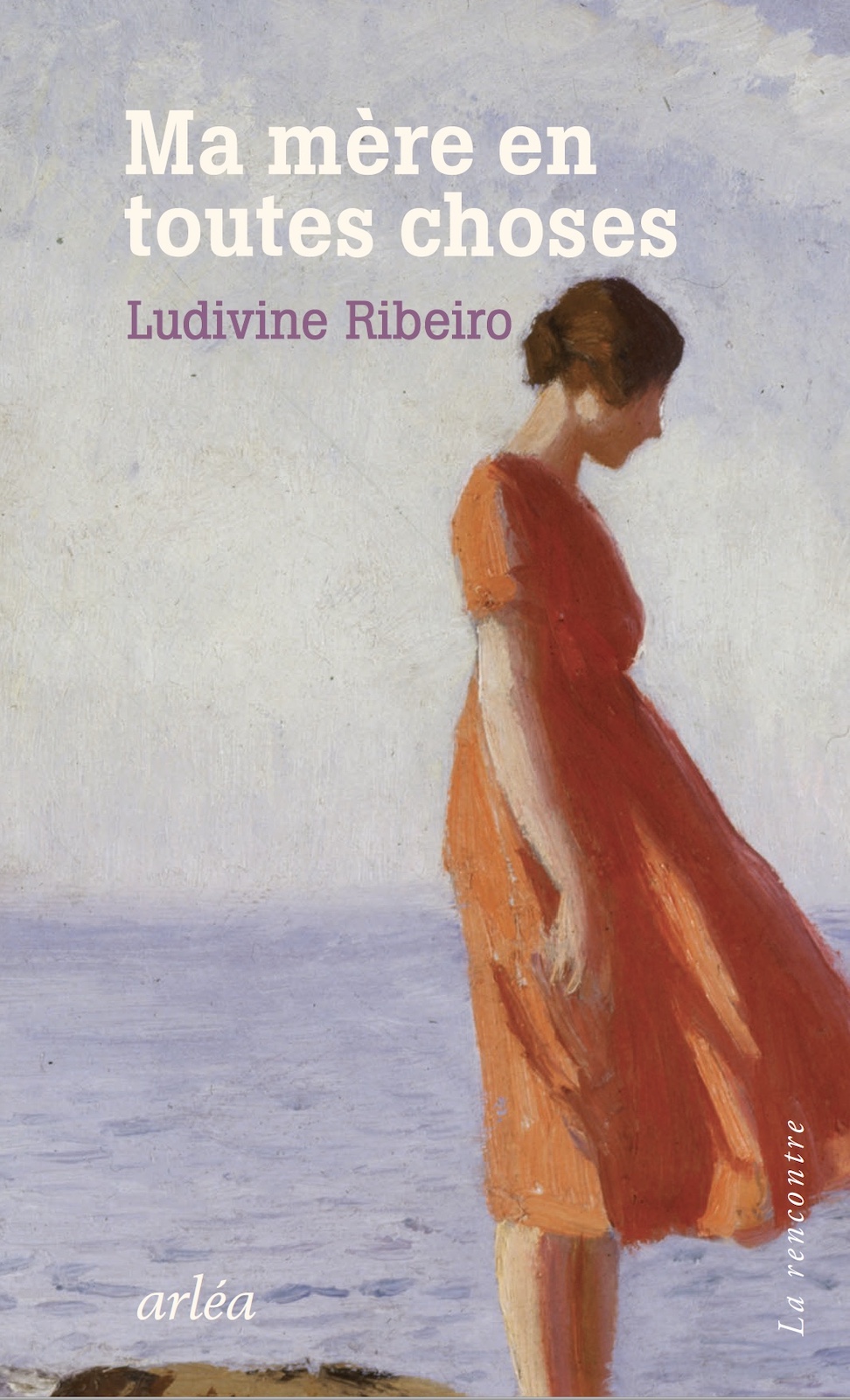

Her mother in all things

Ludivine Ribeiro’s second book, which is launched on 31 August, is not a novel: it’s an experience. Thanks to the objects that belonged to her late mother, which she photographed over many years, the writer was able to overcome the darkest periods of her grief. Far from being self-centred, this book speaks gently to all those who mourn. Isabelle Cerboneschi

How do you survive the death of your most beloved person in the world? Journalist and writer Ludivine Ribeiro lost her mother ten years ago. In her eyes, this loss was inconceivable, unacceptable, unbearable, insurmountable, all at once and even worse.

She patiently built up a collection of objects left to her by her mother, put words to them and turned them into a book – Ma mère en toutes choses – almost without wanting to. The result is tender and deeply moving, and speaks to all those who have found themselves bereft of someone dearer than all else.

INTERVIEW

Talking about your mother through the objects she loved and left you, was it the least painful way of dealing with your suffering?

Ludivine Ribeiro : I wasn’t thinking of doing a book about all that. I was just trying to survive a moment when I was in total panic: my mother was no longer there, I had the impression that she had disappeared off the face of the earth and it was an unbearable thought. Until one day I had this idea: “no, she hasn’t disappeared, look, there are objects all around you that came from her!” I got out my camera and photographed every single thing she had given me or that I had inherited. I started writing words under each one. It grew in size and I could see that something was being built. But that wasn’t the intention at the start.

What convinced you to turn it into a book?

At times it seemed to me that I was touching on something universal. But the process took time: on the day my book comes out (31 August 2023), it will have been ten years since my mother died. For the first few years, I couldn’t write two lines. All I did was take photos. It was only after six or seven years that I managed to write. During those years, friends of mine also lost their mothers. I sent them a few chapters, and even though their experience was very different from mine, I could see that it did them good. That encouraged me to continue. Initially, my manuscript was twice as big: I wanted to do something exhaustive, like a dictionary with all the little pieces of my mother in it that would never disappear. She would be enclosed in a book.

When I read your book, I thought that your mother’s death was recent because you didn’t anchor this moment in time. Was this deliberate?

Yes, because it seems like yesterday to me. It’s as if I’d lost all sense of time in my grief. But the book is chronological: I talk about my feelings, how I felt at the beginning and I evolved over time. But it’s not very precise. There’s a chronology of grief, but it’s not a story: it’s an experience.

Are you aware of the fact that this book has the capacity to awaken in everyone a memory, an object, a smile, and that it creates a link with the bereaved?

No, but it would be nice if that’s what happens when you read the book. It’s a hope I have. The idea isn’t to reawaken the suffering, but to give some pointers on how to survive the most difficult bereavements. There are simple things you can do to keep yourself together.

Do you also feel that we are lied to when we are grieving? People say that things will get better with time, but it’s not true: they never do…

What disturbed me was that I had the impression that the people around me who had lost a parent were coping better than I was, and that I really wasn’t very good at mourning. So I didn’t dare talk about it any more. People told me “in a year, you’ll see, it’ll get better”, but I was getting worse and worse. I don’t know if everyone puts on a brave face so as not to disturb others, or if it’s easier for some people? Losing your parents seems to be a taboo subject, even though we all go through it. We hear all these stories about resilience, about picking up life where it left off, but it’s not true. Life as it was no longer exists.

You write: “We think that mourning is learning to live without, when in fact it’s the opposite. Absence is not the opposite of presence, but presence amplified, exalted, multiplied, and that’s what we have to cope with from now on, this mixture of emptiness and invasion.” Do you feel invaded?

Yes, but without the negative side of invasion. I find that people who have disappeared are more present than others. And when I say they are present, it’s not a malicious or burdensome presence, even though it’s extremely painful. I have the impression that my mother is there all the time, as is my father, who left shortly afterwards… I have the impression that they are with me, sending me signs, protecting me.

What kind of signs, for example?

The working title of my book was “MA”. The publisher thought it was too obscure, so we changed it. On our last holiday, my husband and I went to Italy, where I went as a child and where the book begins. I was by the sea on my mother’s birthday, which is a painful date for me. I was watching the waves when suddenly a large piece of driftwood hit my foot. I tried to pick it up, but it was too heavy. When I tried to pull it out, I saw that there was something written on it and it was engraved ‘MA’. I took some photos and left it in the sea. Of course you could say it was a coincidence, that two lovers called Michel and Alice had carved it, but in the meantime, on my mother’s birthday, this piece of wood with the title of my book arrived as if to say “I’m here”.

Do these signs help you ?

Yes, but you become a bit dependent on them.

How do you explain the feeling of guilt you get when you lose the person you cherished most in the world and you ask yourself: “Why did that person go and not me”?

I can’t explain it. I’ve had survivor’s guilt for a long time. They say it’s normal. That guilt and also the guilt of not having done enough when they were alive.

You write: « The memories of me being a child left with her, there’s nothing left of me being young anywhere. Nobody looks at me as a child any more. And there’s another part of me to mourn, that part of me that’s gone, that no loving memory can bring back to life”. But in the end, talking about your mother is also talking about yourself and remembering the little girl you once were?

But I can’t remember me without her! I don’t remember what I was like, what kind of character I had, what I liked or didn’t like, except what she told me about myself. Sometimes I’d like to ask her something, but I can’t any more. She was the memory of me and of the family, too. It’s like the hard drive on your computer disappearing: things are lost. In today’s world, it’s strange because we have the impression that we can find everything with our friend Google. But he knows nothing about me as a child, or my family history, or my mother. Google knows nothing about people who aren’t famous.

Why Google?

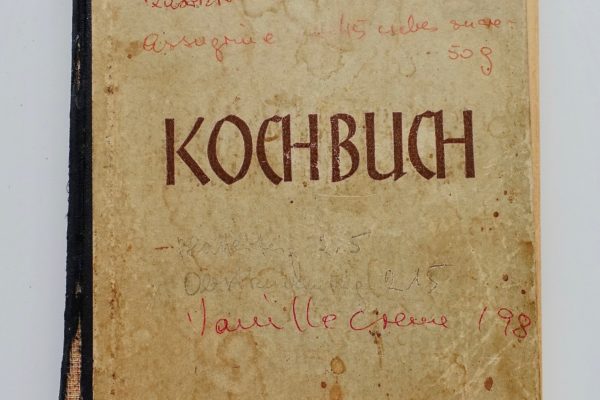

Because it has helped me a lot. Before, I used to call my mother all the time to ask her trivial things that I couldn’t remember, like “How long do you cook the beans for? I’ve got into the habit of asking Google the same question and it answers me. It’s a small relief, but I can’t ask everything.

Do you remember any special saying?

She was born in Brombach, in the Black Forest, and she left me several, like this one: “Morgen früh ist die Nacht vorbei”, “Tomorrow the night will be over”, she would sometimes say, although we both know that’s not always true.

You write that you are looking for “a secret logic in numbers, a mysterious equation that could explain everything, finally giving meaning to all the dramas, all the separations”. Have you found this famous hidden meaning?

Not yet, but I’m sure there is one. I think one day I’ll find it.

How can we survive all this?

I’ve no idea. It seems to me that we shouldn’t survive such terrible grief: you should be pulverised on the spot and yet, strangely enough, you survive. I find that both marvellous and shocking. I try to see the wonderful side of it. My mother would have wanted me to look at that side.

Ma mère en toutes choses, Ludivine Ribeiro, ed. Arléa, août 2023