Kimono rocks

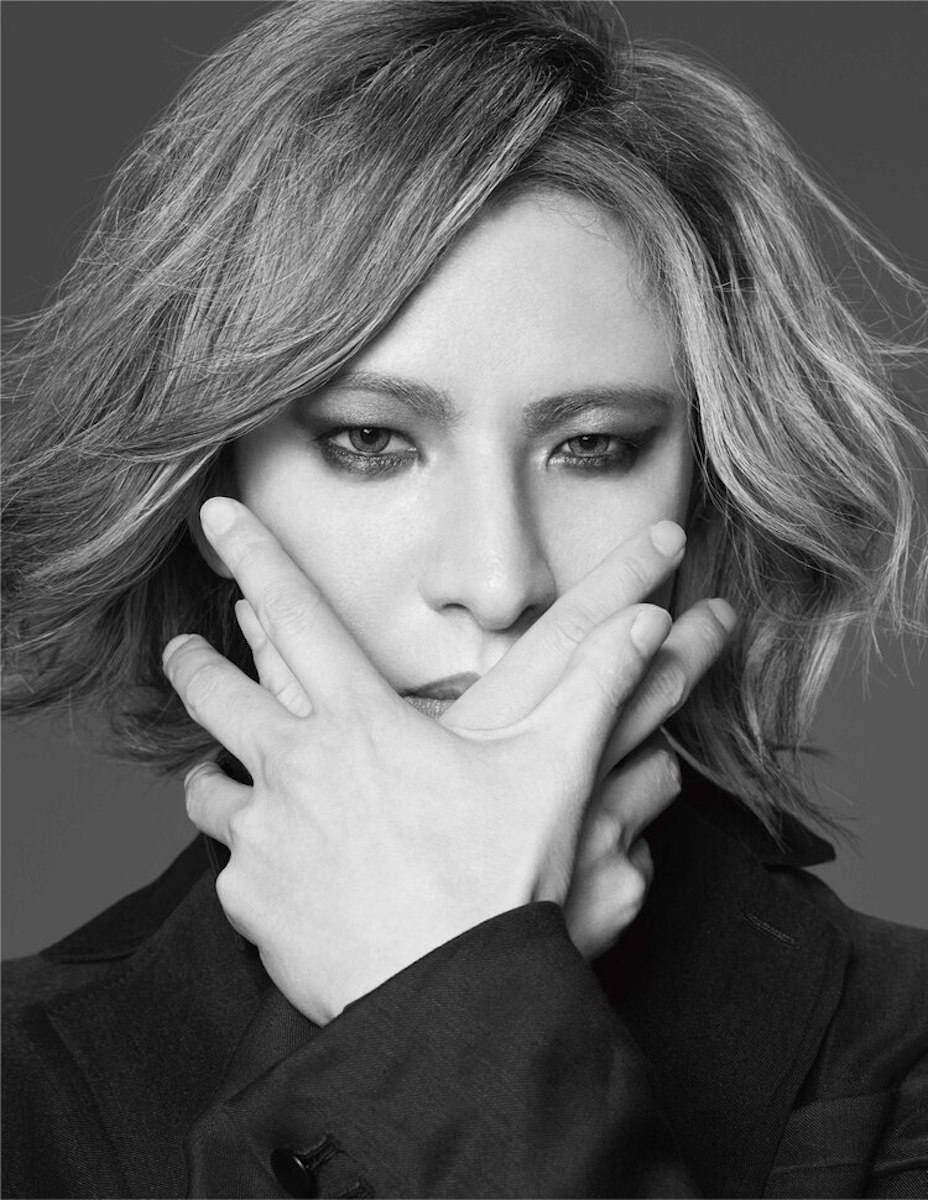

Last spring, almost another era, the “Kimono” exhibition opened at the Victoria & Albert Museum. In the meanders of the millennial history of this exceptional garment, which inspired Paul Poiret as much as Yoshikimono’s creations, imagined by Yoshiki, the legendary leader of X Japan. A fantasy? Far from it. Virtual encounter with an artist with multiple talents and deep roots like the story of this garment whose traditional rock’n’roll expression haunts the memory of an exhibition. Lily Templeton, London.

Being the eldest son of a kimono merchant, Yoshiki was meant to take over the family business. But the muses choose otherwise. At the age of 10, the encounter with a KISS album sealed the first part of his destiny: it was music that first called him. As a piano virtuoso, trained in classical music, his talent was such that he was invited to play before the Emperor and Empress Emeritus of Japan in 1999.

And yet, at that time, he was already a much more radical icon in his country. It was as a pioneer of Visual Kei, a form of gesamtkunstwerk in which performance is as important as the music itself, that Yoshiki made his name internationally. As a Christmas gift in the year 2020, he is currently offering a virtual concert in which he has invited personalities as varied as Marilyn Manson, Scorpions, the violinist Lindsey Stirling, or St. Vincent for a digital Christmas concert organized for his fans.

And the kimono in all these musical twists and turns? To see Yoshiki as the only musical icon would be to forget that decompartmentalizing is the only fixed point in everything he accepts. For the sake of argument, imagine if David Bowie had become a fashion designer, and you’ll have an idea of the brand Yoshikimono. Launched in 2011, with the highly respected factory Keigo Kano, it only presents collections when its creator wants to express himself.

Then radical transformations or wa inspiration, this peaceful unity within a group in search of a collective harmony that transcends personal interests, one should only read in these themes and variations the singular will of an artist who makes his arts – music as kimono – fields as alive as immortal.

You are known for your phenomenal musical career. Why did you decide to also create kimonos about ten years ago?

Yoshiki Being the son of a kimono merchant, you could say that fashion has been in my blood since birth. I see fashion in everything I do. Even when I compose music, it’s a form of fashion. But while I respect kimono history, which is an irreplaceable part of Japanese culture, I don’t want to take it any less into the future, in the same way that the classical piano finds its place in my music alongside the drums so dear to rock.

Dans In the exhibition, you can see that these clothes are transmitted from generation to generation. Is the kimono the original eco-responsible clothing?

That’s a question I could have asked my great-great-great-ancestor. But when I compose a rock piece or a classical piano concerto, I’m always thinking about creating something that will still be alive in hundreds of years, like Beethoven’s or Tchaikovsky’s scores. I can easily imagine that my ancestors saw their work in the same way, with the same vibe. Some say of me that I am a perfectionist, a perpetual unsatisfied. But it is this state of mind that one must have when creating, whether it be in music or in fashion.

The kimono has inspired fashion brands and designers throughout history and around the world. What do you think about this?

I would need to study more before I can say whether the kimono has really influenced those who have been inspired by it. But if this garment had an echo of the magnitude you describe, I would feel honored as a descendant of a family of kimono makers.

How do you translate the values, both aesthetic and philosophical, that guide the kimono’s forms into a contemporary language?

Big question. I keep the traditional form but I try to drastically transform the wearer. In terms of fabric, I looked beyond the materials used traditionally. Regarding the motifs, as you know, I integrated Japanese animation. I think there’s always a fine line between rejecting tradition and innovating.

To give a parallel with the other side of my career, I come from classical music. When, a long time ago, I rearranged and played a Beethoven piano sonata, it created controversy. But people eventually came to accept this style. It’s so difficult to keep the authenticity of classical music by trying to find your own way. In my case, [innovating] is my way of showing respect for the original artist. The word disruption is probably an overused word, since it is used as a label for any innovator. But I think it’s the only one to describe the way I’ve always envisioned going through this world. I think it’s the only way I can keep myself away from death.